In this article

The Freerider route El Capitan stands as a monumental challenge and a coveted prize in the world of rock climbing. This comprehensive guide aims to unpack the allure of this iconic big wall free climb, providing experienced climbers with the essential knowledge for a successful ascent. We will explore its storied history, delve into the technical demands of its pitches, outline gear requirements, and discuss the strategic planning necessary to tackle this granite behemoth on El Capitan. Prepare to understand what makes Freerider a true test of free-climbing prowess.

Core Understanding of the Freerider Route

This section delves into the fundamental details of the Freerider route, defining its scope, key geographical features, prominent figures associated with it, and the essential climbing lexicon involved. It will establish a foundational knowledge for climbers to build upon, ensuring a clear understanding of the Freerider route on El Capitan. This route is a significant objective for many.

Defining Freerider: Scope and Characteristics

Freerider is renowned as El Capitan’s most popular and, in relative terms, “easiest” free route. Climbers typically encounter a grade of VI 5.13a or 5.12d (Yosemite Decimal System), depending on the variations chosen for the ascent. The route stretches approximately 1000 meters (3300 feet) across the southwest face of El Capitan, encompassing 30-35 pitches; specifically, the route follows complex crack systems up the southwest face of El Capitan.

The path largely follows the historic Salathé Wall but incorporates crucial variations. These deviations, notably bypassing the harder free climbing on the Salathé Headwall, make Freerider consistently free climbable as a somewhat separate route from the original Salathé line. This particular route plan focuses exclusively on a free ascent. First conquered in its free form by Alexander and Thomas Huber in 1998 – one of the most notable first free ascents in Yosemite history – the Free Rider (VI 5.13a; 3,000ft) offers a diverse array of climbing styles on immaculate granite. Free climbers will navigate slabs, cracks of all sizes, stemming corners, and sections of face climbing. This plan specifically excludes detailed aid climbing strategies, in-depth comparisons to other El Cap climbing routes beyond the Salathé context, general Yosemite tourist information, and dedicated solo climbing strategies, though references to Alex Honnold’s ascent are included for context. For a broader understanding of climbing in the area, a Yosemite National Park climbing overview offers valuable information. More specific Freerider route details and history can deepen your knowledge. Aspirants should have a grasp of climbing in Yosemite National Park.

Key Geographic Features and Route Sections

The Freerider journey commences with the “Freeblast,” covering pitches 1 through 10 or 11. This initial section, often climbed as a standalone objective or a notable stand-alone Yosemite challenge, features slab and crack climbing, leading to Mammoth Terraces and the significant bivy spot, Heart Ledges. Mid-route, climbers encounter the distinctive Hollow Flake, a long pitch characterized by a downclimb and a wide crack. Further up, The Ear, a chimney feature, and the notorious Monster Offwidth present substantial challenges. Important bivy ledges in this segment include Lung Ledge and The Alcove, near El Cap Spire.

The upper cruxes present a choice: the “Boulder Problem” (also known as the Huber Pitch), rated V7 or 5.13a, which involves technical crimpy moves and often a dynamic lunge (dyno). Alternatively, climbers can opt for the “Teflon Corner,” a 5.12d pitch demanding insecure stemming techniques. An article on understanding a boulder problem can clarify this crux type. Higher still, the sustained Enduro Corner(s) test 5.12 endurance, followed by The Block bivy ledge. Climbers then navigate the exposed Roundtable Ledge/Traverse and another challenging Scotty Burke Offwidth before reaching the summit of Capitan. A visual El Capitan route map and features can be very helpful. For those tackling the initial pitches, Freeblast slab climbing details are available.

Prominent Climbers and Their Influence

The first free ascent (FFA) of Freerider was accomplished by brothers Alexander and Thomas Huber in 1998, establishing it as a premier free climb and setting a formidable standard. Their vision in identifying the variation that bypasses the difficult Salathé Headwall was crucial to creating the route as a more accessible El Capitan free climb. This achievement provided a benchmark for future free ascents.

Alex Honnold’s 2017 free solo ascent catapulted Freerider to global fame. His feat showcased the route’s inherent challenges and his meticulous preparation and mental strength; any variations he took when he chose to solo Freerider are of high interest to many a free solo climber. Steph Davis marked a significant achievement as the first woman to free-climb Freerider. More recently, Barbara “Babsi” Zangerl achieved the first flash ascent of El Capitan via Freerider, demonstrating current elite standards and effective strategies. Tommy Caldwell has also had notable ascents and link-ups involving this iconic line. These climbers’ accomplishments inspire and illustrate the route’s enduring appeal and evolving standards in the climbing world. Understanding their contributions adds rich historical context to any route plan. Details on Alex Honnold’s Freerider free solo details are widely documented. Similarly, information on Barbara Zangerl Freerider flash ascent is available.

Essential Terminology: Grades and Styles

Freerider’s difficulty is typically graded using the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS). It is rated 5.13a if one tackles the Boulder Problem variation, or 5.12d for those opting for the Teflon Corner. The route also carries a commitment grade of VI, signifying a long and serious undertaking that requires multiple days on the wall. Specific boulder problems encountered on the route, such as the “Boulder Problem” pitch itself, are often given V-grades, for instance, V7. A solid grasp of these grading systems is crucial for accurately assessing the route’s formidable challenge.

Success on Freerider demands proficiency in a wide array of climbing styles. These include trad climbing, big wall free climbing, and various forms of crack climbing—ranging from finger and hand cracks to fist jams and offwidth sections. Climbers will also encounter delicate slab climbing, insecure stemming corners, and technical face climbing, necessitating a versatile skillset. Familiarity with these terms and the techniques they imply is vital for adequate preparation for such committing routes. For those new to placing their own protection, understanding trad climbing is fundamental. Further information regarding Yosemite climbing grade information and an overview of climbing styles can be found through dedicated resources.

Detailed Pitch-by-Pitch Beta for Freerider El Capitan

This core section provides a detailed breakdown of the Freerider route, pitch by pitch or by major section, including grades, characteristics, and crucial climbing beta. It aims to give climbers a clear understanding of what each part of the ascent entails, essential for navigating the Freerider route pitch by pitch on El Capitan.

The Freeblast (Pitches 1-10/11)

The Freeblast section typically encompasses pitches 1 to 10 or 11, with difficulties ranging from 5.7 to 5.11c. This initial part of Freerider is frequently climbed as a route in its own right and concludes at Mammoth Terraces. Key challenges include polished slabs and thin cracks that demand technical footwork and careful route finding. Pitch 4 presents a 5.11b/c slab crux; the Half Dollar, a 5.10b feature, is found on Pitch 7; and a notable 5.10d downclimb leads to Heart Ledges on Pitch 9.

Pitch 10 involves a tricky 5.11c move to get off Heart Ledges. Some climbers, like Alex Honnold during his free solo, have discovered variations on the Freeblast slabs to bypass insecure sections, showcasing strategic adaptation. The presence of fixed lines on the Freeblast can sometimes offer an early retreat option if necessary. Understanding the character of these initial pitches is crucial for pacing and overall strategy on the main wall above. For those seeking detailed accounts, Freeblast El Capitan pitch details offer insights, and a Freerider overall route topo gives a broader view.

Heart Ledges to The Alcove/El Cap Spire (Pitches ~11 to ~20)

After completing the Freeblast, Pitch 11 is often a 5.1 scramble leading to the base of the iconic Hollow Flake. The Hollow Flake itself, typically spanning pitches 12-14, is a long and memorable 5.11d testpiece on this part of the Freerider route. This section involves a significant downclimb inside the flake, followed by climbing back up an awkward, sometimes poorly protected wide crack or chimney section where gear placements can be sparse or tricky.

Following the Hollow Flake, subsequent pitches lead towards “The Ear,” a distinct chimney feature. Further on, climbers encounter the Monster Offwidth, around pitches 16-17. This notorious 5.11d pitch often starts with a downclimb that guards a sustained 5.11a offwidth section. The Monster Offwidth is approximately 200ft long and is typically climbed left-side in, demanding specific techniques and large cams, such as #6 and #7 Camalots. This demanding block of pitches culminates with sections leading to good bivy spots like El Cap Spire or The Alcove. For those preparing for these unique challenges, researching Hollow Flake climbing strategy and Monster Offwidth detailed beta is advisable. Some essential climbing training equipment could be relevant for preparing for varied crack climbing.

The Cruxes & Upper Headwall (Pitches ~21 to Summit)

Departing El Cap Spire, Pitch ~19 is often a challenging “sandbagged” 5.11c tight hands pitch, frequently chosen over an easier 5.11a offwidth option, leading towards Freerider’s main crux section. Climbers then face a critical choice for pitches ~22-23: the Boulder Problem (Huber Pitch) or the Teflon Corner. The Boulder Problem is the harder, more common option at 5.13a (V7), a short, technical, crimpy slab/face climb often involving a dynamic “ninja kick” or jump. The Teflon Corner, the original Salathé free crux at 5.12d, involves extremely technical and insecure stemming and smearing on glassy rock and can be wet in spring.

Following the crux, The Sewer (Pitch ~23/24) is a 5.11a pitch, often wet, involving crack climbing and chimneying to a roof, then steep hands to The Block bivy. Then come the Enduro Corners (Pitches ~25-26), two sustained and pumpy challenges; the first is typically 5.11c/d, and the second is 5.12b, demanding endurance and power-laybacking skills. Near the top, climbers navigate the Roundtable Traverse (Pitch ~27), a radical and exposed 5.12a traverse, and the Scotty Burke Offwidth (Pitch ~29), another classic and hard 5.11d offwidth high on the route. The final pitches to the summit are typically around 5.10d. For insights on Freerider Boulder Problem technique or Enduro Corner climbing footage, video resources can be helpful. Context on understanding climbing difficulty is also relevant here.

Essential Gear for a Freerider Free Ascent

This section details the necessary climbing hardware and soft goods required for a multi-day free ascent of Freerider. It will cover everything from the trad rack to bivy essentials, ensuring climbers are well-equipped with their Freerider route gear list for El Capitan.

The Trad Rack: Cams, Nuts, and Slings

A comprehensive trad rack is absolutely crucial for Freerider, typically including doubles or even triples of cams up to the #3 or #4 Camalot size (or equivalent brands). Specific large pieces, such as a #5, #6, and sometimes a #7 Camalot, are essential for particular pitches like the Monster Offwidth and the Hollow Flake. Offset nuts, alongside a standard set of nuts, are vital for the varied and often irregular crack systems encountered on Yosemite granite.

Alpine draws are generally preferred over standard quickdraws due to their versatility in extending placements, which helps reduce rope drag on wandering pitches and assists in managing the rope effectively. A sufficient number of slings of various lengths are also necessary for building anchors and managing gear throughout the ascent. While the precise number of each cam size can vary based on free climber preference and strategy, having a robust selection, especially in hand and finger sizes, is key for tackling the route’s 30-plus pitches. For those building their initial setup, resources on building your first trad rack are useful, as is an El Capitan trad rack discussion. A general overview of essential climbing gear for mountains can provide additional context.

Ropes, Hauling, and Bivy Equipment

For the lead line, a single dynamic rope, typically 60m or 70m in length, is common for direct pitches. However, a tag line, which can be static or semi-static, is essential for hauling gear up the wall of El Capitan. This second rope can also be used for managing rope drag on traversing pitches or for facilitating retreats if such a situation becomes necessary. Bivy gear choices depend heavily on the team’s strategy. While Freerider can be climbed using natural ledges if a 4-5 day strategy is employed, a portaledge is an optional item that can enhance comfort or provide bivy options where natural ledges are small or sloping. Sleeping bags and pads appropriate for Yosemite conditions are mandatory for any multi-day ascent.

Efficient hauling gear is critical for conserving energy over the long haul. This includes a durable haul bag of adequate capacity and an efficient pulley system, such as a Petzl Pro Traxion or a similar setup, to make the process smoother and less strenuous. A stove for preparing food and melting snow (though water hauling is more common than finding snow on Freerider) is also a standard part of the bivy kit. Learning about how to big wall climb hauling systems and understanding climbing pulley systems explained are valuable. When choosing the right climbing rope, understanding static vs. dynamic ropes is key.

Personal Climbing and Safety Gear

Each climber must have a helmet, a comfortable and reliable harness, and multiple pairs of climbing shoes. Different shoe types can be beneficial for the varied free-climbing styles on Freerider (e.g., stiffer shoes for edging, softer shoes for smearing/slabs). Appropriate clothing layers are essential for managing the variable weather conditions on El Capitan, which can range from intense sun and heat to cold winds and precipitation. This includes base layers, mid-layers, and a waterproof/windproof outer shell.

A reliable headlamp with spare batteries is crucial for any climbing that might extend into the dark, for navigating bivy chores, or for early starts and late finishes. Crucially, wag bags for human waste are mandatory in Yosemite National Park for all multi-day climbs. Climbers must pack out all human waste and trash to comply with Leave No Trace principles. Familiarizing oneself with Yosemite wilderness permit requirements and Leave No Trace climbing ethics is part of responsible preparation. Proper gear like selecting a rock climbing helmet is a critical aspect of personal safety.

Logistics and Strategic Planning for Freerider

This section focuses on the strategic elements of executing the climb, from approach and descent to multi-day ascent pacing, bivy management, and essential considerations like water, food, and permits. Proper planning logistics for the Freerider El Capitan ascent is paramount.

Approach, Descent, and Route Pacing

The approach to the base of Freerider typically begins from El Capitan Meadow, involving a hike to the toe of El Capitan’s southwest face. This initial effort needs to be factored into the first day’s energy expenditure. For the descent, options primarily include the East Ledges descent, which takes 2-4 hours and involves rappels and scrambling, or the longer Yosemite Falls Trail, requiring 4-5+ hours. Each has its pros and cons regarding technicality, length, and footwear requirements.

Common multi-day ascent strategies to climb Freerider are 3, 4, or 5-day plans. A popular 4-day plan might utilize bivy ledges such as those near the Hollow Flake (or Mammoth Terraces for an earlier bivy), El Cap Spire/The Alcove, and The Block higher up. Pacing is critical; climbers must balance moving efficiently with conserving energy for the crux pitches and sustained difficulties encountered high on the route. Carrying an extra day’s supplies can be a wise contingency. For further reading, Freerider route general logistics and discussions on El Capitan descent options discussion are helpful.

Bivy Ledge Beta: Capacity and Comfort

Key natural bivy ledges on Freerider include Mammoth Terraces, which are large and situated at the top of the Freeblast, and Heart Ledges, a significant spot after the Freeblast. Higher up the route, options include Hollow Flake Ledge (smaller), The Alcove (a good spot often used before tackling the upper cruxes), El Cap Spire (a prominent spire and ledge system), and The Block (located higher on the route before the final pitches).

It’s important to research the capacity and comfort of these ledges; some are spacious, while others can be sloping or more exposed, potentially impacting rest quality. Information gleaned from trip reports and guidebooks is invaluable here. The choice of bivy ledges will directly influence daily climbing objectives and the overall ascent strategy. Some climbers may opt to haul a portaledge for guaranteed comfort or if natural ledges are expected to be crowded on popular routes like this one. While Long Ledge is another known El Capitan bivy, it is more relevant to the Salathé Wall Headwall pitches, which Freerider avoids. Sous Le Toit is another higher bivy option to consider. For firsthand accounts, Freerider trip report bivy experiences and El Cap Spire bivy details can offer insights.

Water, Food, Waste, and Permits

Water planning is a critical component of a Freerider ascent, with a typical recommendation being 1 gallon (or 4 liters) of water per person per day. Given the multi-day nature of the climb, this translates to hauling significant weight up the wall. Some parties employ strategies like stashing water and food at Heart Ledges in advance; this can be done by climbing the Freeblast section and then fixing ropes or rappelling down to retrieve them later. Food should be high-energy, easy to prepare, and palatable after several days on the wall; careful calorie planning is important to maintain energy levels.

The mandatory use of wag bags (human waste disposal bags) and packing out all human waste and trash is a strict Yosemite National Park regulation and a core Leave No Trace principle. A Yosemite National Park Wilderness Permit is required for all overnight big wall climbs, including Freerider. These are typically obtained via self-registration at designated permit stations, but it is essential to check the latest National Park Service guidelines for any changes. Understanding Yosemite wilderness climbing permit information and tips for Big wall food and water planning is beneficial. Adherence to understanding rock climbing ethics is paramount.

Sun, Shade, and Timing Strategy

Freerider is located on the southwest face of El Capitan, meaning it receives significant sun exposure, especially during the afternoon hours. This solar radiation can make certain pitches or sections extremely hot and strenuous to climb. A critical strategic element involves planning to climb heat-sensitive pitches, such as the Monster Offwidth or the polished Freeblast slabs, during cooler parts of the day or when they are in the shade.

Understanding how sun exposure affects different parts of the route throughout the day and across different seasons is vital for optimizing performance and managing water consumption effectively. This might involve early morning starts for sections that catch the morning sun or timing climbs on particularly sunny walls for late afternoon shade, if possible. Alternatively, climbers might accept the heat and plan to carry more water for their El Capitan adventure. Information on Yosemite seasonal weather patterns and strategies for managing heat on big wall climbs can aid in this planning.

Required Skills, Training, and Preparation

This section outlines the physical, technical, and mental attributes required to attempt Freerider, along with guidance on how to cultivate them through specific training and building experience. Adequate training and skills for the Freerider route El Capitan are non-negotiable for any free climber considering this objective.

Essential Climbing Proficiency and Techniques

Climbers aspiring to Freerider should possess a solid ability to redpoint 5.12 trad routes consistently and comfortably. Experience leading up to 5.13a is necessary if attempting the Boulder Problem variation of this free route. Comfort and competence on varied granite climbing styles are absolutely essential for both success and safety on such a demanding route. Mastery of specific techniques is required: confident slab climbing for the Freeblast, proficient crack climbing in all sizes from finger to fist, and solid offwidth technique for formidable pitches like the Monster and Scotty Burke.

Stemming corners, such as the Enduro Corners, demand endurance and specialized movement patterns. Furthermore, technical face climbing skills are crucial for successfully navigating cruxes like the Boulder Problem. Proficiency in Yosemite granite styles is particularly important, as the climbing can be nuanced and uniquely demanding. For targeted improvement, rock climbing finger training techniques can be beneficial. Seeking Freerider specific training advice and studying advanced rock climbing techniques will also aid preparation.

Big Wall Skills and Systems Management

Efficient big wall systems are non-negotiable for a route like Freerider. This includes smooth and practiced hauling techniques to conserve precious energy over multiple days on the wall of El Capitan. Competence in short-fixing, if applicable to the team’s chosen strategy, along with building and managing multi-pitch anchors swiftly and securely, are paramount skills. Effective rope management throughout long and complex pitches is also crucial for efficiency and safety.

If using a portaledge, climbers must be adept at its setup, breakdown, and the logistics of living comfortably on it. Even without a portaledge, managing life on small natural ledges for several days requires organization and practice to maintain well-being and efficiency. The ability to manage sustained exposure over many hundreds of meters for multiple days is a significant psychological component of big wall free-climbing that should not be underestimated. A solid grasp of understanding climbing pulley systems is essential for efficient hauling. Learning about building big wall anchors effectively and seeking advice for climbing El Capitan from experienced climbers can further bolster preparation.

Physical, Mental, and Strategic Training

Physical training for Freerider must focus on developing exceptional endurance for long days involving many pitches of sustained climbing. Power for crux moves, specific strength for challenging offwidths and finger cracks (utilizing tools like fingerboard repeaters), and strong core strength are also vital components of a well-rounded physical preparation program. Mental training is equally important. This encompasses visualization of pitches and movements, effective fear management strategies, the ability to maintain sustained focus under pressure, and strong problem-solving skills for unexpected challenges that may arise on the wall. Commitment and resilience are key to pushing through difficult sections or setbacks during an ascent.

Strategic training involves building extensive experience on shorter, yet challenging, Yosemite routes or other granite big walls such as Astroman, The Rostrum, Moonlight Buttress, or The Diamond before attempting Freerider. This progression helps hone both technical skills and big wall systems in a less committing environment than El Capitan. Anticipating and planning for specific cruxes, like the V7 Boulder Problem or the Enduro Corners, with targeted exercises can significantly improve the chances of success. Incorporating strength exercises for climbing into your regimen is beneficial. Insights from other climbers regarding training for Freerider insights and even looking into Alex Honnold’s training regimen can offer valuable perspectives.

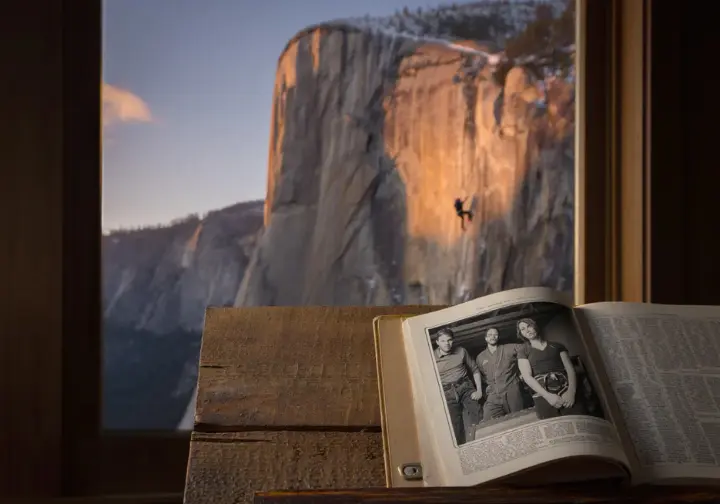

Historical and Cultural Impact of Freerider

This section explores the rich history of Freerider, detailing its first free ascent, the groundbreaking free solo by Alex Honnold, and other notable ascents that have cemented its place in climbing lore. The Freerider route history El Capitan is a significant part of modern climbing and the free-climbing movement.

The First Free Ascent: The Huber Brothers

Alexander and Thomas Huber made the groundbreaking first free ascent (FFA) of Freerider in May 1998. This landmark achievement established the route as a premier and viable free climb on the imposing granite monolith of El Capitan. They completed the ascent in a remarkable 15 hours and 25 minutes, a very fast time for that era, showcasing their exceptional skill and visionary approach to big wall free climbing.

The Huber brothers’ ascent was particularly significant because it identified key variations, particularly around the Salathé Headwall. These variations made a continuous free line possible at a more attainable grade than freeing the original Salathé Wall directly. Alex Huber reportedly identified this Freerider variation while attempting the Salathé. Their pioneering spirit set new standards in the discipline and opened the door for countless other climbers to aspire to the challenge of Freerider. For more context, Huber brothers Freerider FFA details and Freerider first ascent context offer further reading.

Alex Honnold’s 2017 Free Solo Phenomenon

Alex Honnold’s free solo ascent of Freerider on June 3, 2017, completed in an astonishing 3 hours and 56 minutes, was a monumental event that resonated far beyond the climbing community. This audacious feat brought unprecedented global attention to the route and to the sport of climbing itself. Honnold’s preparation was meticulous, involving years of rehearsing the route while roped, memorizing complex sequences of moves, and even developing specific variations on pitches to make sections more secure for a ropeless ascent. Examples of these adaptations include his variation on the Freeblast slabs and a lower entry into the Monster Offwidth. Many consider his one of the most significant free solo ascents of all time.

His ascent serves as a profound case study in risk assessment, mental control, and absolute dedication to a singular goal. While the free solo itself is an outlier achievement, his strategic adaptations and targeted training offer valuable lessons that can be applied to roped free ascents as well. It’s crucial for climbers inspired by the film “Free Solo” to understand the immense difference between a roped free ascent—already a massive challenge—and Honnold’s unique and historic achievement. You can find details of Honnold’s Free Solo preparation and hear from Alex Honnold on free climbing preparation.

Other Notable Ascents and Freerider’s Status

Steph Davis holds the distinction of being the first woman to free climb Freerider, a significant milestone in the history of female big wall climbing and one of many important free ascents on El Capitan. Barbara “Babsi” Zangerl made history with the first flash ascent of El Capitan via Freerider, climbing it free on her first try with prior information, showcasing current elite standards. Her experience, which included adapting beta on the fly, highlights the importance of problem-solving and learning from others’ experiences.

Tommy Caldwell, a prominent figure in Yosemite climbing, has also made notable ascents and link-ups that include Freerider, further solidifying its importance in the climbing world. Freerider is often referred to as “The Astroman for the new generation,” a quote attributed to Alexander Huber. This signifies its status as a benchmark free climb on El Capitan for modern climbers, much like Astroman was for a previous era. Learning about Babsi Zangerl El Capitan flash insights and the history of El Capitan flash attempts can provide deeper context.

Managing Risks: Safety and Contingency Planning

This section addresses the critical aspects of safety and risk management for a Freerider ascent, including common hazards, bail strategies, emergency preparedness, and the importance of partner dynamics. Prioritizing Freerider route safety on El Capitan is fundamental.

Common Hazards on Freerider

Rockfall is an inherent risk on any large granite cliff like El Capitan. Climbers must remain vigilant, especially when other parties are climbing above or during freeze-thaw cycles that can dislodge loose rock. Wearing a helmet at all times is non-negotiable for protection. Unpredictable weather, including sudden storms, extreme heat, or cold snaps, poses a significant hazard. Teams must diligently monitor forecasts and be prepared for rapid changes in conditions that can occur in the mountains of Yosemite.

Fatigue, both physical and mental, can accumulate over multiple days on the wall, potentially leading to impaired judgment and an increased risk of accidents. Proper pacing, consistent nutrition and hydration, and ensuring adequate rest are crucial for mitigating this risk. Difficult route finding, especially if climbers stray off the main line, can lead to lost time, encountering dangerous terrain, and increased exposure to objective hazards. While Freerider is a well-traveled route, knowing the topo and key landmarks is essential. Gear failure, though rare, is possible; regular inspection of personal and team gear is a vital safety habit. Familiarity with Yosemite climbing safety guidelines and awareness of general big wall climbing hazards are key. The importance of a climbing helmet cannot be overstated.

Bail and Retreat Strategies

Knowing potential rappel points and having a clear plan for retreat in case of an emergency—such as severe weather, injury, or unacceptably slow progress—is a critical part of big wall preparation for any route on El Capitan. This involves understanding anchor situations and rappel logistics from various points on the route, should a descent become necessary. Fixed lines on the Freeblast section can offer a relatively straightforward early retreat option for parties encountering difficulties low on the route.

Higher up on Freerider, retreat becomes significantly more complex and committing. It often involves multiple rappels down steep and potentially traversing terrain, which can be challenging to navigate in reverse. Consolidated information on specific, reliable rappel retreat points and current anchor quality for Freerider is not always easy to find, requiring thorough research. Having a tagline is essential for most retreat scenarios; it facilitates rappels and can potentially help retrieve stuck ropes, a common issue on long descents. Teams should discuss bail scenarios beforehand and ensure both partners are comfortable and proficient with the agreed-upon procedures. General information on big wall retreat and bailing techniques is available, and climbers often discuss Freerider specific bail considerations – forum discussion on online forums.

Emergency Preparedness and Partner Dynamics

Climbers attempting Freerider should possess basic self-rescue knowledge and skills, as professional rescue on El Capitan can be complex and time-consuming to initiate and execute. This includes techniques for escaping the belay, various methods of partner rescue, and basic first aid appropriate for a wilderness setting like Yosemite. Reliable communication methods are important, though cell service can be spotty or non-existent on many parts of El Capitan. Some climbers choose to carry satellite communication devices for emergency situations. Awareness of National Park Service emergency procedures is also vital.

Partner competency and communication are paramount for both safety and success on a route of Freerider’s magnitude. Both partners must be skilled, experienced, and able to communicate effectively about decisions, conditions, and their physical and mental state throughout the climb. Pre-trip discussions should thoroughly cover expectations, individual risk tolerance, detailed emergency plans, and specific responsibilities to ensure both climbers are aligned and prepared to function as a cohesive team. Solid partner dynamics include effective belaying techniques. For broader knowledge, the American Alpine Club offers resources on climbing emergency preparedness, and blogs often discuss the importance of partner communication in climbing.

Climbing Sustainably: Ethics and Environmental Responsibility

This section focuses on responsible climbing practices within Yosemite National Park, emphasizing Leave No Trace principles and the Yosemite Climber’s Credo to ensure the preservation of Freerider and its environment for future generations. Practicing sustainable Freerider route climbing practices is a duty for all who visit El Capitan.

Leave No Trace (LNT) on a Big Wall

Applying Leave No Trace (LNT) principles is crucial in the unique vertical environment of a big wall like Freerider on El Capitan. This goes beyond simply not littering and involves proactive measures to minimize impact on the fragile granite ecosystem. A primary responsibility is packing out all trash, including food wrappers, used tape, and any other refuse generated during the multi-day ascent. Nothing should be left on ledges or thrown off the wall.

Critically, all human waste must be packed out using approved wag bags or portable toilet systems. This is a mandatory regulation in Yosemite National Park and is essential for protecting water sources and maintaining the aesthetic quality of the routes for everyone. Climbers should strive to minimize chalk marks by using it judiciously, brushing off excess chalk from holds where possible, and considering the use of colored chalk that blends with the rock if it is available and accepted by the local climbing community. Furthermore, avoid damaging any vegetation found on ledges or along the route. Understanding the general rules of rock climbing and ethics is a good starting point. For more specific guidance, consult resources on Leave No Trace principles for rock climbers and responsible chalk use in climbing.

Adhering to the Yosemite Climber’s Credo

The Yosemite Climber’s Credo is a set of community-developed ethics for climbing within Yosemite National Park. It emphasizes respect for the environment, fellow climbers, and the rich history of climbing in the Valley. Adherence to this credo is expected of all climbers visiting this special place, particularly on iconic routes like Freerider. Key tenets often include minimizing physical impacts on the rock, such as avoiding excessive drilling or intentional altering of holds, and respecting wildlife and vegetation encountered on and around the climbs of El Capitan.

The credo also promotes consideration for other climbing parties. This includes managing noise levels, avoiding unnecessary delays if a faster party is behind, and sharing bivy ledges respectfully if space is limited. Responsible use of fixed gear is another important aspect; this can involve removing old, rotting slings and replacing them with earth-toned, durable materials, and generally not adding unnecessary fixed gear to established routes. For those wishing to learn more, resources detailing Yosemite climbing ethics and practices and official Yosemite National Park climbing regulations are available.

Route Traffic and Inter-Party Etiquette

Freerider is one of El Capitan’s most popular free climbs, which means encountering other parties on the route is highly likely, especially during peak climbing seasons. This high traffic requires patience, good communication, and a cooperative mindset from all climbers on the wall. Strategies for dealing with other parties include clear and early communication at belays, politely discussing passing intentions, and being prepared for potential waits at popular stances or crux pitches where bottlenecks can occur on busy routes.

If your party is moving significantly faster than a team ahead, politely inquire about the possibility of passing at a convenient and safe location, such as a large ledge or an easy pitch. Conversely, if a faster party is approaching from behind, try to facilitate their passage when it is safe and reasonable to do so without compromising your own party’s safety. Choosing less popular bivy ledges if possible, or being prepared to share larger ledges considerately, can also help manage congestion and ensure a more pleasant experience for everyone. Overall, a respectful and cooperative attitude contributes significantly to a better experience for all climbers sharing the vertical world of El Capitan. For perspectives on managing crowds on popular climbs and general climbing etiquette guidelines, further reading is available.

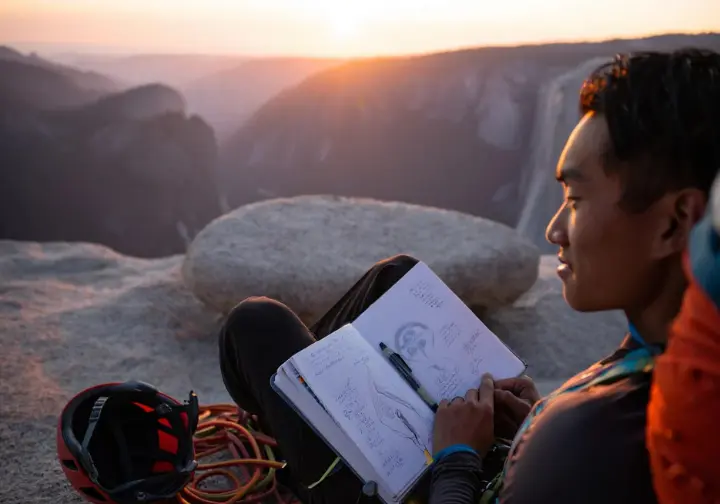

The Freerider Journey: A Developmental Framework

This section reframes the Freerider route plan as a developmental journey, exploring how the process of preparing for, planning, and attempting this iconic climb builds a comprehensive and transferable skillset for climbers. It aims to offer learning opportunities beyond just ticking the route, focusing on developing skills via the Freerider El Capitan route.

Skill Development Beyond Sending

The process of targeting a challenging route like Freerider inherently fosters significant skill development, regardless of achieving a perfect first-try free ascent. This approach aligns with cultivating a growth mindset in climbing, where learning and improvement are paramount. Climbers develop advanced technical proficiency across diverse styles, including delicate slab work on the Freeblast, strenuous offwidth thrutches on pitches like the Monster, powerful crack jamming in various sizes, and precise face climbing on cruxes. This hard-won versatility is highly transferable to other challenging climbing routes worldwide.

The logistical planning required for a multi-day big wall ascent – managing gear, food, water, time, and complex on-wall systems – builds invaluable organizational and strategic decision-making capabilities. Mental fortitude, including sustained focus under pressure, creative problem-solving when faced with unexpected challenges, effective fear management, and resilience in the face of setbacks, is profoundly cultivated throughout the entire Freerider journey. Enhancing rock climbing skills and safety involves continuous learning. Insights on learning from challenging climbs and understanding the mental aspects of big wall climbing can be beneficial.

Strategic Decision-Making On and Off the Wall

Successfully navigating Freerider requires climbers to make numerous strategic decisions, both during the extensive planning phase and while actively on the route. This goes far beyond simply following a topo and involves continuous assessment and adaptation for this specific El Capitan free route. Climbers must learn to analyze options carefully, such as choosing between the Teflon Corner and the Boulder Problem cruxes. This decision should be based on their individual strengths and weaknesses, current conditions like weather and route traffic, and their personal risk tolerance for different styles of difficulty.

On-the-wall decision-making is equally critical. This includes judging when to push through accumulating fatigue versus taking an unscheduled rest, figuring out how to adapt to unexpected challenges like a wet or unexpectedly difficult pitch, or when to make the difficult but sometimes necessary call to bail from the route. The ability to assess risk accurately and make sound judgments under pressure is a key skill honed by the experience of big wall free-climbing. This capacity is essential for long-term safety and continued success in the demanding mountain environment. Understanding decision making in high consequence environments and general risk assessment in climbing offers valuable perspectives.

Learning from Setbacks and “Imperfect” Ascents

Not every attempt on Freerider results in a perfect, first-go free ascent, and there is immense learning value in experiences that involve setbacks, mistakes, or not sending every pitch free. Trip reports from various climbers often detail challenges such as battling dehydration, encountering unexpected difficulties on certain pitches, the intense mental battle after taking falls on a crux, or needing to significantly adapt plans due to weather, partner issues, or unforeseen circumstances during their ascents. These relatable accounts offer realistic perspectives on what an ascent can entail.

Embracing resilience, adaptability, and the overall learning process is crucial for growth as a free climber. Understanding common mistakes that others have made can help future aspirants avoid similar pitfalls in their own planning or execution when they try to climb Freerider. This reflective approach fosters a deeper understanding that extends beyond simply ticking a route off a list. It aligns with a developmental journey where every experience, successful or not, contributes to becoming a more competent and well-rounded climber. While focused on a different discipline, the principles of improving climbing skills through structured training and learning from weaknesses apply broadly. Reading Freerider trip report challenges and lessons or a learning from climbing mistakes forum can provide valuable real-world context.

Key Takeaways for Conquering Freerider

This concluding section summarizes the most critical takeaways from this comprehensive route plan. Freerider presents a multifaceted challenge that demands a high-level of free climbing ability across diverse styles. It also requires robust big wall logistical skills, significant physical endurance, and strong mental fortitude to overcome its many obstacles. Meticulous planning and thorough preparation are absolutely paramount for any team aspiring to this iconic El Capitan free route.

This preparation includes a detailed pitch-by-pitch understanding of the route, strategic gear selection tailored to Freerider’s specific demands, well-thought-out logistics for a multi-day ascent (covering food, water, bivy sites, and waste management), and specific physical and mental training regimens. Learning from the experiences of others, both elite climbers who have pushed the standards and “everyday” strong climbers who have undertaken the challenge, provides invaluable insights into crux strategies, managing unforeseen difficulties, and adapting plans when necessary. Embracing the entire “Freerider Journey” as a developmental process, focusing on skill acquisition and strategic thinking, offers profound growth opportunities regardless of the immediate outcome of any single attempt to free-climb this line. Finally, climbing Freerider responsibly, by strictly adhering to Leave No Trace principles and the Yosemite Climber’s Credo, is essential to preserve this iconic route and its magnificent environment for future generations of climbers.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Freerider Route El Capitan

What is the main difference in difficulty between the Boulder Problem and Teflon Corner cruxes on Freerider? >

How many days does it typically take to free climb Freerider, and what are common bivy spots? >

What are the most critical pieces of gear specific to Freerider’s challenges on El Capitan? >

Besides physical strength, what are the key mental skills needed for Freerider? >

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We also participate in other affiliate programs. The information provided on this website is provided for entertainment purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, adequacy, legality, usefulness, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information, or about anything else. Any reliance you place on the information is therefore strictly at your own risk. Additional terms are found in the terms of service.