In this article

Climbing’s rewards are immense, but inherent risks demand our attention. Drawing from extensive research and accident analysis, we’re exploring the top 10 climbing dangers & life-saving prevention strategies to equip climbers of all levels with essential knowledge and actionable climbing accident prevention. Fostering a culture of safety enables sustainable participation in this often risky activity, and that starts with understanding how human factors, climbing equipment integrity, technical proficiency, and environmental awareness critically prevent common climbing accidents. Consider this your comprehensive resource for identifying major hazards and implementing life-saving techniques across various climbing disciplines—from leader falls to overuse injuries. Continuous learning is key for every climber, so let’s delve into these crucial areas to make every adventure and ascent safer.

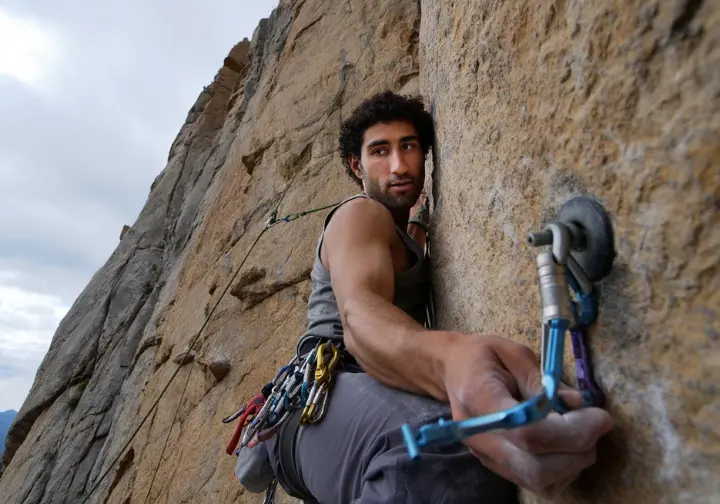

Danger 1: Leader Falls – Understanding and Mitigating Risks

Leader falls present a primary concern in roped climbing, with outcomes varying from minor injuries to severe trauma or even fatalities. Examining common causes, such as ground falls and ledge impacts, alongside crucial prevention strategies, helps in understanding how to minimize these significant dangers and their potential causes. Understanding fall protection in these scenarios is a fundamental climbing skill.

Common Causes and Contributing Factors of Leader Falls

Inadequate or poorly placed protection stands as a major cause, where gear fails under load due to bad rock quality, incorrect placement like cams walking or pulling out, or an insufficient number of pieces. Protection points spaced too far apart can also lead to dangerously long falls, increasing the risk of impact; indeed, big ledges can be just as dangerous as the ground. For a deeper dive into how these falls occur, consider reviewing an analysis of climbing fall dynamics.

Belayer error significantly contributes to the severity of leader falls. This includes providing too much slack, inattention leading to delayed reaction, or incorrect belay device operation, any of which can result in a ground fall or a hard impact with the rock. Understanding these common roped climbing accident causes is essential for every climber. These belay mistakes can turn a manageable trip up a wall into a serious incident.

Climbing ropes and their management are critical; issues such as excessive rope drag making clipping difficult or extending falls, or the rope running behind the climber’s leg causing an inversion, can turn a manageable fall into a dangerous thing. Misjudging the difficulty of moves or climbing to the point of exhaustion also increases fall likelihood, particularly when transitioning to outdoor lead climbing.

Environmental hazards like wet or loose rock can compromise handholds and footholds, while climber-specific factors include misjudging climbing route difficulty or physical condition. Furthermore, a lack of communication between the climber and belayer regarding readiness or potential difficulties exacerbates these risks.

Life-Saving Prevention for Leader Falls

Develop proficiency in placing solid protection, considering rock quality, direction of pull, and potential fall forces. Always aim for redundancy in crucial placements and understand concepts like fall factors to minimize impact forces during a fall. This is a key aspect of risk management awareness.

Master effective rope management to prevent excessive drag by using appropriate length slings and extending placements where necessary. Maintain constant awareness of the rope’s position relative to your body to avoid tripping or inversion during a fall, which is critical for safety. This is an important aspect of performance climbing.

Ensure your belayer is attentive, experienced in dynamic belaying techniques appropriate for the situation, and that clear, standardized communication is established before starting the climb. For those looking to refine their technique, there are expert tips on dynamic belaying available. This includes discussing potential cruxes or areas where a shorter rope might be beneficial, as well as choosing appropriate belay devices.

Accurately assess routes against your current physical and mental abilities, and be willing to retreat if a climb feels too committing or conditions deteriorate. Avoid climbing when excessively fatigued, as this significantly impairs judgment and physical performance, impacting your ability to make safe decisions. Always consider the risk versus reward.

Danger 2: Belaying Errors – The Unseen Link

As a critical safety function, belaying demands precision; errors here can have catastrophic consequences for the climber. Understanding common belaying mistakes and the essential techniques for their prevention is key, emphasizing attentiveness and proper training to address frequent climbing accidents and their prevention. This is a dangerous aspect of climbing—the potential for sudden issues if attention wavers.

Common Types and Consequences of Belay Errors

One of the most catastrophic errors is losing control of the brake strand, which can lead to dropping the leader. This often happens due to inattention, incorrect hand positioning, or being overwhelmed by a sudden fall. Such accidents highlight the need for constant caution.

Providing too much slack in the system is a frequent error that can result in the leader falling further than necessary, potentially hitting the ground (a ground fall) or dangerous ledges. This critical misjudgment can stem from miscalculating the climber’s needs or simple distraction during the belay process. This can lead to serious damage.

Incorrect operation of the belay device, including improper loading of the rope or mishandling specific device features (especially with assisted braking devices), can lead to device failure or inability to catch a fall effectively. Inattention or distraction, such as talking to others or focusing on things other than the climber, is a major contributing factor to many belaying incidents, as highlighted by real examples of belay errors (Page 10-11, “Lowering errors becoming more common”).

Errors during lowering, such as an uncontrolled descent, lowering the climber off the end of the rope (if stopper knots aren’t used or rope length is misjudged), or miscommunication leading to the climber being taken off belay prematurely at an anchor, are also significant sources of accidents. These are crucial points for mastering fundamental belay techniques.

Essential Prevention Techniques for Belayers

Undergo comprehensive training in belay techniques for various devices, ensuring you understand the nuances of both tube-style and assisted braking devices (ABDs). Your brake hand should never come off the brake strand of the rope unless the climber is securely anchored. This training is part of essential climbing accident prevention.

Always perform meticulous pre-climb partner safety checks, including verifying harnesses are correctly worn and buckled, knots are properly tied and dressed, and the belay device is correctly threaded and attached to the belayer’s harness with a locking carabiner. Use clear, standardized, and closed-loop communication throughout the climb, where commands are repeated and confirmed. Following official climbing safety guidelines is key.

Maintain unwavering attention on the climber, especially when they are close to the ground, above ledges, or navigating difficult sections. Avoid all distractions, such as cell phones or conversations not related to the climb, as these can have severe consequences. Diligence here is a lifesaver.

Be aware of rope length in relation to the pitch length to prevent lowering a climber off the end of the rope; always tie a stopper knot in the end of the rope as a critical backup. Consider anchoring the belayer in situations with high potential fall forces, poor stances, or significant weight differences. These are core principles of safe belaying and good risk management.

Danger 3: Rappelling/Lowering Accidents – The Descent Dilemma

A significant number of serious climbing accidents happen during rappels or lowering, frequently due to preventable errors in setup or procedure. Highlighting typical accident types and crucial preventative measures promotes safer descents, showing how to avoid rappelling accidents and lowering mishaps. These rappel errors are a catastrophic safety concern for many.

Types of Rappelling and Lowering Accidents

Rappelling off the ends of the rope is a common and often fatal mistake. This can occur due to unequal rope lengths, misjudging the length needed to reach the next anchor or the ground, or simply forgetting to tie stopper knots. The importance of stopper knots in rappelling cannot be overstated.

Incorrect setup of the rappel device or its attachment to the harness is another critical error. This includes misthreading the rope, attaching the device incorrectly, or issues with the carabiner connecting the device to the harness. An analysis of rappelling accident causes often points to these simple mistakes.

Losing control during the descent, perhaps due to hair or clothing getting caught in the device, a sudden slip, or inability to manage friction effectively, can lead to rapid, uncontrolled descents and serious injury. Anchor failure during the rappel or lower, though less common if anchors are assessed, can also have catastrophic consequences.

Miscommunication during a lowering sequence is particularly hazardous. For example, a belayer might mistakenly take the climber off belay before they are secured at an anchor, or there might be confusion about who is doing what, leading to the climber being dropped. Such things can lead to avoidable accidents.

Critical Prevention Measures for Safe Rappels and Lowers

Always tie substantial stopper knots (e.g., double fisherman’s or barrel knots) in both ends of the rope before beginning any rappel. This simple step provides a critical backup if you misjudge the rappel length. This is a core tenet of safe rappelling practices.

Consistently use a backup system, such as a friction hitch (e.g., prusik, autoblock, kleimheist) applied to the rope below the rappel device and connected to your harness leg loop. This hitch can arrest your descent if you lose control of the rappel device. Extend the rappel device from your harness with a sling to prevent interference between the device and the backup hitch; this reflects an international focus on climbing safety standards detailed by the UIAA guidance on safety commissions.

Meticulously double-check the entire rappel system—anchor integrity, rope threading through the anchor and device, carabiner locked, harness buckles secure—before committing your full body weight. Crucially, have your partner perform a check as well. Weight-test the system while still secured to the anchor whenever possible. These precautions are vital.

Ensure clear, unambiguous, and closed-loop communication for all lowering operations. Confirm that the belayer understands the plan and that the climber is ready to be lowered. Before being taken off belay after a pitch, ensure you are properly secured to the anchor system, often using personal anchor systems safely, if you are not immediately rappelling or being lowered.

Danger 4: Anchor Failures – When the Lifeline Fails

Anchor failure, whether in traditional (trad) or fixed (bolted) climbing, is a high-consequence event. Examining the causes of anchor failures and outlining essential prevention strategies, including proper building techniques and diligent inspection, is vital for understanding and avoiding anchor failure in rock climbing.

Causes of Trad and Fixed Anchor Failures

Improperly constructed traditional anchors are a significant risk. Common errors include failing to meet SERENE/ERNEST principles (Solid, Equalized, Redundant, Efficient, No Extension / Timely), relying on a single point of protection, poor equalization leading to shock-loading of individual pieces, or placing gear in weak or suspect rock. This is why building bombproof trad anchors is a critical skill for technical rock climbing.

Failure of fixed anchors often results from wear and tear over time. This includes worn bolt hangers, old or UV-degraded webbing (tat), or bolts that were poorly placed initially. Such wear can lead to catastrophic failure of life safety equipment.

Corrosion is a serious and often hidden danger for fixed anchors, particularly Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) in stainless steel bolts, as detailed in the UIAA analysis of anchor failures. SCC can occur in certain environments (e.g., seaside crags, areas with acidic rock or specific mineral content) and can lead to sudden, brittle failure of bolts that may appear sound externally.

Shock-loading in-situ gear of unknown quality or age, such as old pitons or bolts whose history is uncertain, can also lead to failure. Climbers must be wary of relying on any single piece of fixed gear without careful assessment.

Prevention: Building and Assessing Safe Anchors

For traditional anchors, adhere rigorously to the principles of redundancy, equalization, and strength (e.g., SERENE/ERNEST). Use multiple, independent pieces of gear placed in solid, trustworthy rock, and ensure the load is distributed as evenly as possible among them, using advanced techniques for placing cams and nuts.

When encountering fixed anchors, conduct a thorough visual and tactile inspection of all components: bolts, hangers, chains, and any webbing. Look for signs of wear, corrosion (rust, pitting, cracks), loose bolts, or damaged hangers. This is a vital safety check.

Understand the different types of bolts and their susceptibility to corrosion, especially in specific environments like coastal areas or those with acidic rock, like the AAC info on bolt corrosion at specific crags (e.g., Long Dong, Taiwan SCC issues). Be particularly cautious of older stainless steel bolts in environments known for SCC.

Always be prepared to replace old or suspect fixed webbing (tat) with your own material, as UV degradation and weathering can severely weaken slings over time. If in any doubt about the integrity of a fixed anchor, back it up with additional gear if possible, or choose an alternative descent. Adhere to UIAA recommendations for bolting and anchor assessment for additional safety.

Danger 5: Rockfall & Icefall – Hazards from Above

Rockfall and icefall are objective hazards present in most climbing environments, posing a significant risk of impact injury. A review of their causes and crucial preventative actions, with helmet use being paramount, shows how to protect against rockfall and icefall, which are common hazards in mountain climbing.

Causes and Triggers of Rockfall and Icefall

Natural dislodgement is a primary cause, driven by processes like weathering (freeze-thaw cycles, wind, water erosion) or animal activity disturbing loose rocks or ice. This is particularly prevalent in mountainous terrain and areas with chossy or fractured rock. The Mountaineers advice on avoiding rockfall offers valuable insights here. These are natural risks.

Climber-induced rockfall is also very common. This can be caused by parties climbing above dislodging rocks, ropes pulling on loose features, or a climber inadvertently loosening a hold or feature during their movement. This can be a real danger on any cliff or wall.

Icefall typically occurs due to warming temperatures causing ice features to become unstable and break off. Climber activity, such as tool placements or vibrations from movement, can also trigger icefall, especially on fragile or stressed ice formations, a common hazard in winter climbing.

Specific terrain features, such as gullies, ledges with loose debris, or areas directly below ice formations or snowfields, are inherently more prone to rockfall and icefall. Recent rainfall or rapid temperature changes can significantly increase the likelihood of these events. The NPS safety for North Cascades climbs often mentions such hazards. For any climb, selecting the best rock climbing helmet is a non-negotiable first step for rock fall protection.

Prevention: Staying Safe from Overhead Dangers

Always wear a climbing helmet designed for climbing in any environment where rockfall or icefall is a possibility—which includes virtually all outdoor rock climb areas and even some indoor climbing gyms with loose holds. This is the single most important preventative measure; helmets save lives. Knowing why your head matters in climbing reinforces this.

Practice careful climbing route selection by consulting guidebooks, local climbers, or online resources for information on known loose areas or rockfall-prone routes. Whenever possible, avoid climbing directly below other parties to minimize risk exposure.

Position belays in sheltered locations, away from direct fall lines of potential rock or ice. Test suspect handholds and footholds with careful, controlled pressure before committing your full weight, especially on loose or chossy rock. General NPS climbing safety at City of Rocks often highlights these environmental hazards.

Move carefully and deliberately when on loose terrain to minimize the chances of dislodging rocks yourself. If you do dislodge rock or ice, or witness it falling, immediately and loudly warn partners and any other climbers below with standardized calls like “ROCK!” or “ICE!”. The NPS advises that if rock falls from above, protect your spine and dont climb looking up.

Danger 6: Gear Failure/Misuse (Excluding Anchors) – When Equipment Lets You Down

Modern climbing equipment is incredibly strong and reliable when used correctly; however, failure or misuse of items like climbing ropes, harnesses, and carabiners can lead to severe accidents. Emphasizing regular inspection, proper use, and timely retirement of gear highlights the importance of gear inspection to prevent accidents and failures. This is crucial for all types of climbing, including sport climbing and mountaineering.

Causes of Climbing Gear Failure and Misuse

Continued use of worn-out or damaged gear is a primary cause of failure. This includes ropes with significant sheath damage, core shots, or flat spots, which necessitates good rope safety, inspection, and retirement practices. Old harnesses or those with frayed webbing or damaged buckles, slings that are past their lifespan or show UV degradation, and carabiners with deep grooves or faulty gates also pose risks.

Incorrect use of equipment is a frequent factor. Examples include improper carabiner loading (e.g., tri-axial loading, loading over an edge, open gate loading), tying knots incorrectly, misusing belay devices in ways not intended by the manufacturer, or creating safety systems with incompatible components. An analysis of a carabiner cutting a rope can be illustrative of unforeseen gear interactions.

Failure to conduct regular and thorough gear inspections means damage or wear might go unnoticed until it’s too late. Climbers may become complacent and skip these vital checks, especially with gear they use frequently. This is a dangerous habit.

Sometimes, evolving gear designs can introduce unforeseen failure modes if not fully understood, as illustrated by incidents involving thin ropes and certain non-round-stock carabiners under specific conditions. Lack of knowledge about a specific piece of gear’s limitations or proper application can also be a factor.

Prevention: Diligent Gear Inspection, Care, and Use

Implement a rigorous system of regular and detailed gear inspection. This involves visual and tactile checks before each climbing day and more thorough periodic inspections for all safety-critical equipment like ropes, harnesses, slings, carabiners, and belay devices. Understanding climbing harness lifespan is part of this process.

Understand the specific limitations, lifespan indicators (often provided by manufacturers or UIAA guidelines), and retirement criteria for each piece of your equipment. Factors like age, UV exposure, chemical contamination, number and severity of falls held, and visible wear all contribute to retirement decisions, as outlined by UIAA safety standards for climbing equipment.

Ensure proper gear storage to prevent premature degradation. Keep gear away from direct sunlight, extreme temperatures, corrosive chemicals (including battery acid or solvents often found in car trunks), and sharp objects.

Promptly retire any gear that is damaged, excessively worn, has been subjected to extreme forces (even if no visible damage), or is outdated according to manufacturer recommendations or current safety standards. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and retire the gear. Ensure correct application and use of all equipment through proper training and regular practice.

Danger 7: Human Error – Complacency & Miscommunication

Complacency, particularly in experienced climbers, and miscommunication between partners are insidious human errors that frequently contribute to accidents. Exploring how these factors manifest and how to actively prevent them through vigilance and standardized practices is key when addressing human error in climbing accidents like complacency. These human habits can undermine even the best safety systems.

Manifestations of Complacency and Miscommunication

Experienced climbers may develop complacency by skipping routine safety checks they once performed diligently, such as verifying knots, harness buckles, or belay device setup, because “they’ve done it a thousand times.” This normalization of deviance can lead to critical oversights.

Making assumptions about a partner’s actions, intentions, or experience level without explicit confirmation is a common pathway to miscommunication. For instance, assuming a partner knows a specific command or procedure, or assuming they have checked the anchor, can be dangerous. It’s vital to know when speaking up about unsafe climbing practices is necessary.

Using unclear, ambiguous, or non-standardized climbing commands can lead to fatal misunderstandings, especially in noisy environments or when climbers are out of sight of each other. Failure to confirm commands (closed-loop communication) further increases this risk. Understanding the importance of climbing ethics and rules can help prevent this.

Becoming distracted while belaying, setting up a rappel, or performing other safety-critical tasks significantly increases the chance of error. The “expert halo” effect, where less experienced climbers are reluctant to question a more experienced climber, or where an expert takes shortcuts, can also compromise safety.

Prevention: Cultivating Vigilance and Clear Communication

Maintain strict, unwavering adherence to safety checks every single time before leaving the ground, regardless of experience level or how familiar the climb or partner is. This includes the climber checking the belayer’s setup and the belayer checking the climber’s harness, knot, and their connection to the rope.

Use standardized, clear, and concise communication protocols. Ideally, employ closed-loop commands where instructions are given, heard, confirmed, and then action is confirmed (e.g., “On Belay?” “Belay On.” “Climbing?” “Climb On!”). The UIAA’s role in climbing safety awareness emphasizes such clear communication.

Actively listen to and confirm information from your partner. Minimize distractions during critical operations like belaying, anchor building, or rappelling. If you need to communicate something complex, do it when it’s safe and you have your partner’s full attention. These universal precautions are vital.

Foster a climbing partnership where questioning, cross-checking, and speaking up about concerns are encouraged, valued, and met with respect, regardless of differences in experience levels, a concept supported by AMGA guidance on resilience and decision making. Consciously avoid making assumptions by verbalizing plans, intentions, and observations, which are part of the secrets to safe climbing adventures.

Danger 8: Human Error – Poor Judgment, Inexperience, Exceeding Abilities

Flawed decision-making, especially when influenced by inexperience, overconfidence, or pushing beyond one’s limits, is a significant contributor to climbing accidents. An examination of these human factors shows how to develop better judgment and mitigate human error stemming from inexperience or poor judgment. Such risk taking without awareness can be costly.

Manifestations of Poor Judgment and Overreach

Selecting climbing routes that are objectively too difficult for one’s current skill level, physical condition, or the prevailing environmental conditions is a common error. This can stem from peer pressure, “summit fever,” or an inaccurate self-assessment of abilities. Even dangers of your local crag can be underestimated by new climbers.

Underestimating environmental hazards, such as rapidly changing weather, poor or loose rock quality, objective dangers in alpine terrain (e.g., avalanche risk, serac fall), or the seriousness of remoteness and potential for self-rescue, can lead to dire situations. These hazards are often present on a mountaineering trip.

Continuing to push upwards when excessively fatigued, dehydrated, hypothermic, or when conditions are clearly deteriorating demonstrates poor judgment. A lack of self-awareness regarding personal physical or mental limits under stress is a key factor here, especially on difficult climbs.

Inexperience, especially when navigating the gym-to-crag transition, or moving to unfamiliar environments, can lead to misjudgments if the climber hasn’t yet developed the specific skills or awareness needed for that context. Overconfidence can also play a role, where past successes lead to underestimation of current risks. This is a common pitfall for recreational climbers.

Prevention: Cultivating Sound Judgment and Self-Awareness

Engage in a process of gradual progression to build skills, experience, and judgment. Don’t try to jump too far ahead in difficulty or commitment level before you are ready. This is one of the foundational steps to learn how to rock climb and crucial for setting realistic climbing goals.

Make honest and objective self-assessments of your abilities, limitations, and current physical/mental state before and during every climb. Seek mentorship from more experienced climbers or professional safety guidance to develop both technical skills and sound climbing judgment. The Mountaineers’ resources on climbing skills can be invaluable.

Conduct thorough pre-climb planning, including researching climbing routes (difficulty, length, protection, descent), checking reliable weather forecasts, assessing current conditions, and understanding logistics like approach and retreat options. Always have a backup plan or be willing to modify objectives. This level of risk management is vital.

Cultivate a willingness to retreat or change plans when conditions deteriorate, if the climb proves harder than anticipated, or if you or your partner are not feeling up to the challenge. Learn to listen to your intuition or “spidey senses”—if something feels wrong, it often is. The goal is to get down safely, not always to reach the top; this is common mountaineering wisdom about mandatory descents. Sometimes the benefits do not outweigh the risks.

Danger 9: Bouldering Falls & Injuries – Ground Level Risks

While bouldering avoids roped climbing’s high-consequence falls, awkward or uncontrolled landings, missed crash pads, and spotter errors can still lead to significant injuries. Looking into common causes and prevention strategies promotes safer bouldering, preventing bouldering fall injuries and ensuring effective spotting. Even in climbing gyms, these risks persist.

Common Causes of Bouldering Fall Injuries

Awkward or uncontrolled landings are a primary cause of bouldering injuries, especially to ankles, knees, and wrists. This can happen from unexpected slips, dynamic moves gone wrong, or simply losing balance at the top of a problem. A guide to preventing bouldering injuries can offer further insight.

Missing crash pads or landing on uneven surfaces between pads, or on rocks/roots hidden beneath pads, significantly increases injury risk. Insufficient pad coverage for the potential fall zone is also a common issue, emphasizing the importance of mastering spotting and crash pad use.

Spotter errors, such as ineffective spotting (not guiding the fall correctly), miscommunication between climber and spotter about intentions or readiness, or the spotter being distracted, can lead to the climber not being protected adequately during a fall.

Falls from significant height (highball bouldering) inherently carry greater risk, even with good padding and spotting. Repetitive impact from multiple falls, even seemingly minor ones, can lead to acute injuries or contribute to chronic overuse issues, particularly in the lower limbs and fingers/wrists, as supported by bouldering injury statistics and patterns. These can impact a climber’s life significantly.

Prevention: Safe Landings, Spotting, and Pad Use

Learn and consistently practice proper falling technique: aim to land on your feet, bend your knees to absorb impact, and then roll onto your back or shoulder to dissipate the force. Tuck your arms in to avoid trying to catch yourself with your hands, which can lead to wrist injuries. These habits make bouldering a little safer.

Utilize good spotting practices. This involves clear communication between the climber and spotter(s) before climbing, the spotter focusing on protecting the climber’s head, neck, and torso, and guiding the fall towards the center of the crash pads rather than trying to “catch” the climber.

Ensure adequate and well-placed crash pad coverage for the entire potential fall zone, paying attention to gaps between pads and uneven surfaces. Carefully inspect landing zones for hazards (rocks, roots, holes) before starting a boulder problem and arrange pads accordingly; knowing how to pick your best bouldering crash pad is key.

Downclimb whenever feasible, especially from the top of problems, to reduce the number and impact of falls. Progress gradually in terms of height and difficulty of boulder problems to allow your body and skills to adapt. Consider the cumulative impact of many small falls.

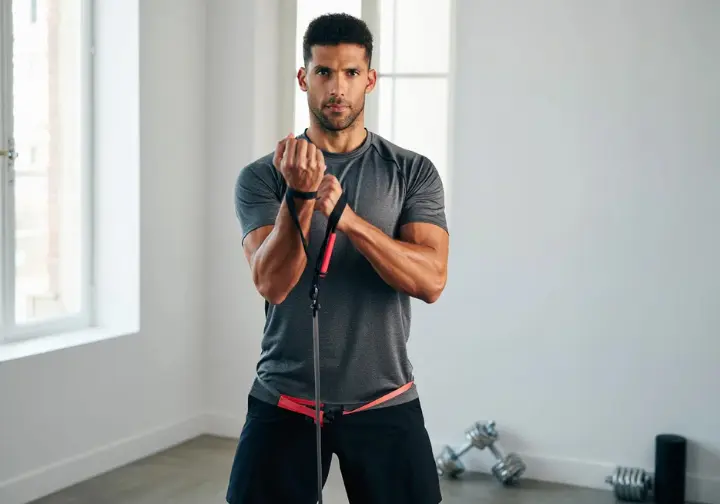

Danger 10: Overuse Injuries – The Slow Burn to the Sidelines

Though not acute accidents, overuse injuries like tendonitis, pulley tears, and shoulder problems are extremely common and can severely limit or end a climber’s participation. Discussing their causes and emphasizing preventative strategies promotes long-term climbing health and shows how to prevent common overuse injuries in climbing. For many climbers, these injuries are a real danger to their climbing goals.

Causes and Types of Common Climbing Overuse Injuries

Repetitive strain on specific tendons, ligaments, and joints from frequent climbing without adequate rest and proper recovery is the primary cause. This is especially true for finger pulleys (A2 pulley tears are common), elbow tendons (medial and lateral epicondylitis or “climber’s/tennis elbow”), and shoulder rotator cuff components. Seeking expert advice on climbing injury prevention can be beneficial.

Poor climbing technique can contribute significantly. This includes excessive or improper use of crimp grips, over-reliance on arms instead of utilizing footwork and core strength, and dynamic movements performed with poor body mechanics, leading to issues like elbow pain from rock climbing.

Significant muscle imbalances, often between strong pulling muscles (lats, biceps, forearms) and weaker opposing/stabilizing muscles (pushing muscles, finger extensors, rotator cuff), can lead to abnormal stress on joints and tendons.

Insufficient warm-up before climbing or a lack of cool-down and stretching afterward can leave tissues unprepared for stress and impede recovery. Rapid increases in training volume, intensity, or climbing frequency without allowing the body to adapt can also trigger overuse injuries.

Prevention: Training Smart for Climbing Longevity

Implement a consistent and thorough warm-up routine before every climbing session, including general cardiovascular activity, dynamic stretching, and climbing-specific movements of gradually increasing intensity. Follow up with a cool-down involving static stretching for key muscle groups.

Incorporate antagonist muscle training into your routine to address and prevent muscle imbalances. This includes exercises for pushing muscles (e.g., push-ups, overhead press) and finger/wrist extensors, as suggested in REI advice on how to climb injury-free. This makes climbing a safer activity long-term.

Actively listen to your body and take rest days or breaks from climbing when experiencing pain, excessive fatigue, or the early warning signs of an injury. Don’t push through pain, as this often worsens the condition. This is an important safety measure.

Refine your climbing technique to use your feet effectively, maintain good body positioning to reduce stress on joints, and vary grip types to avoid over-stressing finger pulleys (e.g., mix open-hand, crimp, and pinch grips). Gradually increase training load and intensity to allow your body’s tissues to adapt over time, employing safe rock climbing finger training techniques. Ensure sufficient sleep and proper nutrition to support recovery and tissue repair.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways for Safer Climbing Adventures

The vast majority of climbing accidents are preventable and often stem from human factors such as complacency, miscommunication, or errors in judgment, highlighting the need for constant vigilance and adherence to safety protocols. Mastering fundamental technical skills (belaying, rappelling, anchor building, gear placement), coupled with diligent partner checks and clear communication, forms the bedrock of climbing safety. Regular and thorough gear inspection, understanding retirement criteria, and using climbing equipment correctly are non-negotiable aspects of risk management in a gear-dependent sport. Cultivating a proactive safety mindset, which includes continuous learning, honest self-assessment, willingness to retreat, and fostering open communication with partners, is crucial for long-term, sustainable climbing. Embrace climbing accident prevention not as a list of restrictions, but as an integral part of skill mastery and a commitment to yourself, your partners, and the climbing community to ensure every climb ends safely.

Frequently Asked Questions about Common Climbing Accidents and Prevention

What is the single most common cause of climbing accidents? +

How often should I replace my climbing rope or harness? +

Is indoor climbing significantly safer than outdoor climbing? +

What’s the best way to learn advanced safety skills like self-rescue? +

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We also participate in other affiliate programs. The information provided on this website is provided for entertainment purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, adequacy, legality, usefulness, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information, or about anything else. Any reliance you place on the information is therefore strictly at your own risk. Additional terms are found in the terms of service.