In this article

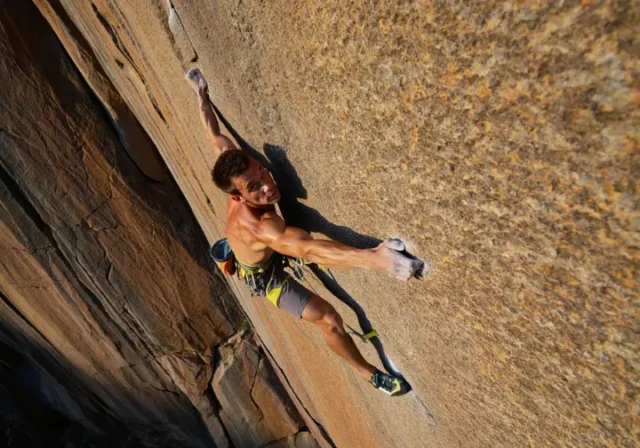

Have you ever felt your hip lock up on a high-step, or a twinge in your shoulder during a wide move, knowing you had the muscular strength but not the movement? This frustrating gap between what your body can do and what it can control is where most climbing injuries happen. Functional Range Conditioning (FRC) is a revolutionary movement system that goes beyond simple stretching to build actively controlled mobility, giving you the joint resilience to prevent injuries and unlock your true climbing potential.

This is not just about becoming more flexible through stretching. It’s about building a stronger, more capable body from the joints out. It’s about turning weak, vulnerable positions into sources of strength and confidence, and improving your overall fitness for sports performance training.

- What FRC Is (and Isn’t): Understand the critical difference between passive flexibility and the active, usable mobility that FRC develops to make you a more efficient climber.

- The Science of Joint Resilience: Learn how FRC trains your central nervous system and remodels connective tissue to build genuinely stronger, “bullet-proof” joints.

- The Core FRC Toolkit: Discover the key exercises—CARs, PAILs/RAILs, and Lift-Offs—that form the foundation of joint health and performance.

- Direct Climbing Application: See exactly how to apply FRC techniques to enhance specific, high-value climbing moves like drop-knees, high steps, lock-offs, and gastons.

What is Functional Range Conditioning (and Why Should Climbers Care)?

Functional Range Conditioning, or FRC, is a comprehensive training system designed to improve mobility, strengthen joints, and enhance body control. For climbers, whose sport demands extreme ranges of motion under load, understanding FRC isn’t just an advantage—it’s a fundamental shift in how we approach physical preparedness, longevity, and athletic performance on the wall. The goal is to move from passive flexibility to active, injury-resistant mobility.

What is the critical difference between active mobility and passive flexibility?

To truly grasp the FRC approach, you must first understand a crucial distinction. Passive flexibility is the range of motion a specific joint can achieve with external help—like gravity, a partner, or using your hands to pull your leg into a deep stretch. This represents your joint’s potential workspace, but it’s a range that is not under your nervous system’s control.

Active mobility, in contrast, is the range of motion you can achieve and control using only your own muscular effort. FRC defines this as your “usable” range of motion; it’s flexibility plus strength. The dangerous chasm between these two is the “Injury Gap”—an uncontrolled zone where your brain cannot safely manage unexpected forces, making it the primary site of sprains, strains, and tears.

FRC’s primary goal is to systematically close this gap. It’s a scientifically proven method that teaches the Central Nervous System (CNS) to “own” and control your existing passive ranges, turning them into safe, functional mobility. This is why it’s more effective for any athlete than traditional static stretching, which often only creates temporary flexibility without teaching control. By understanding the physiological role of sensory nerves, we can appreciate how FRC provides targeted input to the brain. This focus on active control is a cornerstone of building a comprehensive mobility and flexibility program.

| Feature | Passive Flexibility | Active Mobility |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Range of motion achieved with external help (gravity, partner, hands). | Range of motion achieved and controlled using only your own muscular effort. |

| Goal | Increase overall joint range of motion (potential workspace). | Increase *usable* joint range of motion, enhance control and strength within that range. |

| How it Feels | A stretch sensation, often relaxed or slightly uncomfortable. | A sensation of muscular effort and tension, working to move the joint. |

| On-the-Wall Example | Being able to pull your leg up high onto a handhold with your hands. | Being able to place your foot high on a handhold using only your hip and leg strength, maintaining tension and control. |

Who is Dr. Andreo Spina and what is his philosophy?

Dr. Andreo Spina is the creator of the Functional Range Systems (FRS), which includes FRC. With a deep background in kinesiology, chiropractic, and sports sciences, his work is grounded in applying scientific principals and research to optimize human movement and articular health. His core philosophy is elegantly simple: “Force is the language of cells.” This refers to mechanotransduction, the biological process where cells convert mechanical force into chemical signals that drive tissue adaptation in the body.

This philosophy underpins his systems. External Force involves manual therapy, like Functional Range Release (FR®), while Internal Force refers to the voluntary muscle contractions you generate yourself, which is the foundation of Functional Range Conditioning (FRC®). This distinction clarifies that FRC is a self-driven training system for improving mobility. The full FRS continuum progresses logically from assessment (FRA®) and treatment (FR®) to training (FRC®) and its group class application, Kinstretch®. This demonstrates how FRC fits into a complete, professional system for improving movement quality from rehabilitation to athletic performance, a key focus for FRC practitioners. This principle is directly supported by the science behind mechanoreceptors, the very cells that translate force into nerve signals, and is a vital component of any a structured rock climbing training program.

How Does FRC Actually Build Stronger, More Resilient Joints?

FRC’s effectiveness stems from its dual-pronged approach: it simultaneously trains the nervous system to grant more control while also strengthening the physical tissues of the joint itself. This movement-based training system isn’t just about passive stretching; it’s about fundamentally upgrading your body’s hardware and software to avoid injury.

How does FRC train the Central Nervous System, not just the muscles?

The FRC system operates on the principle of Neurological Primacy: your Central Nervous System (CNS) is the ultimate governor of your movement. If the CNS perceives a range of motion as unsafe or weak, it will reflexively restrict access to it by creating stiffness or muscle tightness. Traditional passive stretching might temporarily bully the CNS into submission, but because no muscular control is learned, these gains are fleeting.

FRC, however, is a form of active motor learning involving neuromuscular facilitation. By using specific isometric contractions at your end-range, you are actively “proving” to your nervous system that you can safely produce force in those joint positions. This communication convinces the brain to release its protective brakes and permanently grant you access to that range. Exercises like Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs) are particularly powerful, as the joint capsule is dense with specialized mechanoreceptors for proprioception. These FRC exercises provide high-resolution feedback, updating the CNS’s “map” of the joint’s capabilities and enhancing your kinesthetic awareness—a critical part of a systemic approach to safer climbing.

How does FRC directly strengthen vulnerable end-ranges of motion?

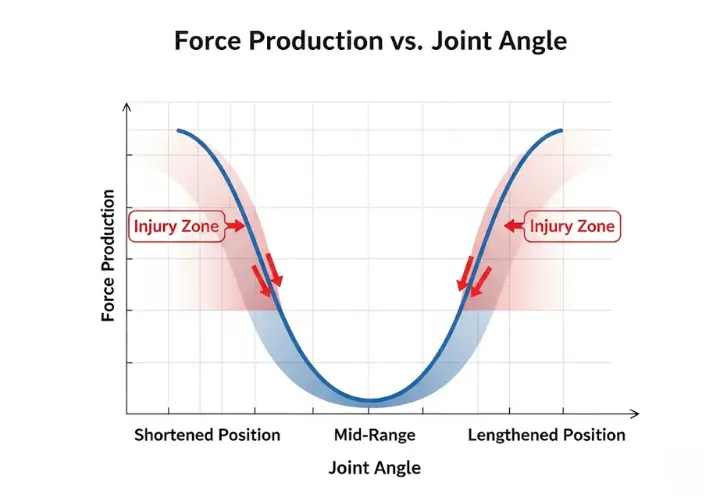

It’s a simple biomechanical fact: muscles are weakest at their extreme end-ranges of motion—the fully lengthened or shortened positions. Unfortunately, these are the exact positions where most athletic movements can lead to overuse injuries. Traditional strength-training often neglects these vulnerable zones, focusing on the powerful mid-range. FRC, by contrast, specifically targets these weak points with dedicated exercises.

The system places direct, targeted stress not only on muscles but also on the non-contractile connective tissues like the joint capsule, ligaments, and tendons. This targeted force application stimulates these tissues to adapt, increasing their load-bearing capacity and resilience. This quality, termed articular resilience, is the hallmark of a healthy joint. FRC is effectively a form of strength training for your joints. By preparing for the awkward, “ugly” positions of a desperate move or a sudden slip, it makes a climber’s body robust and ready for the chaotic reality of the sport, addressing the sources of many research on common rock climbing injuries and helping in preventing common injuries like climber’s elbow.

What Are the Core FRC Exercises Every Climber Should Know?

The FRC system is built upon a toolkit of specific, scalable exercises. For a climber, mastering these three core FRC methods is the first step toward building truly resilient joints and unlocking new levels of movement on the wall. They are the practical application of FRC’s scientific principles in an exercise routine.

What are Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs) and why are they a daily practice?

Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs) are slow, active, and deliberately controlled rotational movements of a joint through its entire, pain-free range of motion. Think of them as “brushing your teeth for your joints.” They serve a critical dual purpose:

- Daily Self-Assessment: CARs are a quick way to check in with your major joints. Do you feel any pinching, clicking, or blocking? This daily feedback allows you to catch potential issues before they become an impending injury.

- Mobility Maintenance: The “use-it-or-lose-it” principle absolutely applies to joint mobility. Daily CARs ensure you maintain the ranges of motion you already have.

Proper execution is key. The whole movement must be slow and maximally controlled. Critically, you must create full-body tension, a principle called irradiation, to isolate the working joint and prevent compensation. As detailed in a climber’s guide to warming up, this type of active movement is an essential part of preparing the body for climbing, making CARs a perfect addition to a structured rock climbing warm-up.

How do PAILs & RAILs actively expand your range of motion?

While CARs maintain your existing mobility, PAILs/RAILs are the primary tool for actively expanding it. This is a powerful sequence of isometric contractions performed at a joint’s end-range, typically after holding a passive stretch for two minutes in a stretched position.

- PAILs (Progressive Angular Isometric Loading): This involves isometrically contracting the tissues that are being stretched. For example, in a hip stretch, you would try to push your leg out of the stretch against an unmovable object, like the floor. This is the PAIL stretch phase.

- RAILs (Regressive Angular Isometric Loading): This is the opposite. You contract the tissues on the other side of the joint, like your hip flexors, to actively pull yourself deeper into the stretch.

This sequence provides powerful feedback to the central nervous system, teaching it how to produce force in these new, previously inaccessible ranges. This is the process that converts passive flexibility into usable, active mobility. For a clear breakdown of the protocol, see this an explanation of PAILs and RAILs. This technique is a core component of our integrated mobility strength training program.

How do Lift-Offs and Hovers build strength at your end-range?

Once you’ve created a new range of motion with PAILs/RAILs, you must strengthen it to make it permanent and useful. This is the job of end-range strength training, with Lift-Offs being a cornerstone exercise for climbers.

After achieving a passive end-range position, a Lift-Off involves actively lifting the limb off a surface without any momentum. This requires a maximal contraction of the shortened tissues and directly builds strength and control where you are typically weakest. An initial step can be Passive Range Holds, where you passively move a limb to its limit and then simply try to hold it there actively. A more advanced progression, Hovers (like a shoulder hover), adds a dynamic component, like lifting a limb over a small obstacle, further challenging your control. This focus on end-range training is a good strength progression and is crucial for joint stability, aligning with expert advice on strengthening exercises for climbers and forming a key part of our guide to strength exercises for climbing.

How Can FRC Directly Improve Your Climbing Technique?

The true value of FRC for climbers is its direct, measurable impact on performance. By systematically improving joint capacity in the hips and shoulders, we can unlock more efficient, powerful, and safer complex movements on the wall. Here is how FRC principles translate into better execution of high-value climbing techniques.

How does FRC unlock powerful hip-driven moves like drop-knees and high-steps?

As noted by physical therapists, hip mobility as a climber’s secret weapon, allowing us to keep our weight close to the wall, reduce the load on our arms, and move with greater efficiency. FRC provides the tools to develop this weapon and give your tight hips a complete hip mobility overhaul.

- For High Steps: A fluid high step requires strong, active hip flexion. The FRC solution is building end-range hip flexion strength with exercises like Hip Flexion Passive Range Holds and Lift-Offs, giving you the power to place your foot precisely on a high hold without jerking your leg.

- For Heel Hooks: This move demands a combination of hip flexion and external rotation of the thigh. Using PAILs/RAILs in positions like the 90/90 hip position expands this usable range, allowing for more secure and powerful heel placements.

- For the Drop-Knee: The drop-knee is a direct expression of active hip internal rotation. The most targeted FRC intervention is the 90/90 Hip Internal Rotation Lift-Off, which specifically trains the pelvis and surrounding muscles for this notoriously difficult range, giving you the ability to rotate your right hip into the wall for maximum reach.

These powerful hip movements are only effective when stabilized by developing a strong climber’s core, which transfers force from the lower to the upper body.

How does FRC create stable shoulders for lock-offs and gastons?

Many climbers suffer from “Climber’s Posture”—forward, rounded shoulders from an imbalance of strong pulling muscles (like the biceps) and weak postural ones. This leads to impingement and instability, which FRC directly addresses. Clinicians often see these patterns when resolving common climbing injuries.

- For a strong Lock-off: A stable lock-off depends on rotator cuff and scapular control, meaning stable shoulder blades. Daily Shoulder CARs improve neurological control, while end-range strengthening for external rotation (moving the arm backward) builds the rock-solid stability needed to hold difficult positions.

- For a safe Gaston: The gaston places the shoulder joint in a vulnerable, internally rotated position. Using PAILs/RAILs for internal rotation builds strength and tissue resilience in this specific, compromised position, making the move safer and more powerful.

- For a powerful Mantel: The crux of a mantel is the vulnerable transition from pulling to pushing, which requires significant shoulder extension. FRC addresses this by using PAILs/RAILs for shoulder extension, building the necessary tissue capacity to handle the extreme load at that specific end-range.

A stable shoulder is the foundation for the entire kinetic chain, allowing for more effective force transfer all the way down to your forearms and hands when integrating finger training techniques.

| Climbing Problem | The Problem | The FRC Exercise |

|---|---|---|

| Lock-off | Lack of rotator cuff and scapular control for static holds. | Daily Shoulder CARs (Controlled Articular Rotations); End-range strengthening for external rotation. |

| Gaston | Shoulder placed in vulnerable, internally rotated position under load. | PAILs/RAILs for internal rotation (building strength and resilience in this specific end-range). |

| Mantel | Vulnerable transition from pulling to pushing, requiring significant shoulder extension. | PAILs/RAILs for shoulder extension (building tissue capacity at the extreme end-range). |

Conclusion

Functional Range Conditioning offers climbers a paradigm shift away from simply chasing flexibility in impressive poses towards a more intelligent, scientific pursuit of usable mobility. By understanding and applying its principles, you are no longer just stretching; you are actively communicating with your body to build a more resilient and capable version of yourself.

- FRC builds active, controllable mobility, not just passive flexibility. This closes the “Injury Gap” and is superior for athletic performance.

- The system works by training the Central Nervous System to grant control over new ranges of motion and by applying targeted force to strengthen connective tissues.

- The core toolkit includes daily CARs for maintenance, PAILs/RAILs for expanding range, and Lift-Offs for solidifying gains with end-range training.

- For climbers, this translates directly to better performance and safety in crucial movements like drop-knees, high steps, and lock-offs by building the necessary joint capacity.

Explore our complete library of Mobility and Strength Training guides to build a truly comprehensive and resilient climber’s body.

Frequently Asked Questions about FRC for Climbers

Is FRC the same as yoga?

No, FRC is not the same as yoga, though they can be complementary. FRC is a targeted scientific system for improving joint function on a joint-by-joint basis. Yoga is a holistic practice that includes flexibility, balance, and mindfulness. You can apply FRC principles of active muscle engagement and control within your yoga poses to make it even more effective for building usable mobility.

How often should a climber do FRC?

The frequency depends on the exercise. CARs should be a non-negotiable daily practice, like brushing your teeth, performed as part of a warm-up or as a separate joint hygiene routine. More intensive work like PAILs/RAILs and end-range strengthening should be treated like any other strength training and performed 2-3 times per week with adequate rest.

What is the difference between FRC® and Kinstretch®?

Kinstretch® is the group-class application of FRC® principles. Think of FRC® as the overarching system, often applied one-on-one by a certified professional to assess and address an individual’s specific mobility deficits. Kinstretch® is the system packaged into a group fitness class workout, designed to be taught by an FRC-certified instructor for general mobility improvement.

Can I start FRC on my own at home?

Absolutely. Daily CARs are the perfect starting point and can be safely practiced at home or in the gym. They are a powerful tool for self-assessment and maintenance. However, for addressing specific injuries or creating a targeted program using more advanced FRC techniques, seeking guidance from a certified FRC Mobility Specialist (FRCms) is highly recommended to ensure safety and effectiveness.

Risk Disclaimer: Rock climbing, mountaineering, and all related activities are inherently dangerous sports that can result in serious injury or death. The information provided on Rock Climbing Realms is for educational and informational purposes only. While we strive for accuracy, the information, techniques, and advice presented on this website are not a substitute for professional, hands-on instruction or your own best judgment. Conditions and risks can vary. Never attempt a new technique based solely on information read here. Always seek guidance from a qualified instructor. By using this website, you agree that you are solely responsible for your own safety. Any reliance you place on this information is therefore strictly at your own risk, and you assume all liability for your actions. Rock Climbing Realms and its authors will not be held liable for any injury, damage, or loss sustained in connection with the use of the information contained herein.

Affiliate Disclosure: We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. We also participate in other affiliate programs. Additional terms are found in the terms of service.