In this article

Every dedicated climber eventually hits the wall. Not the one in the climbing gym, but the frustrating, invisible barrier where simply trying harder and climbing more yields nothing but fatigue and frustration. This is the plateau. Many climbers find the solution isn’t more of the same; it’s a fundamental transition from exercising to structured training. This framework provides a step-by-step guide, built on the proven science of periodization, to help you design a personalized, year-long training plan that will systematically dismantle your weaknesses, help you climb harder, and have you peaking for your specific climbing projects.

- Understand the Science: Learn the core principles like Progressive Overload and Supercompensation that make structured training effective.

- Choose Your Blueprint: Compare Linear, Block, and Undulating periodization models to find the one that best fits your goals and lifestyle.

- Build Your Personalized Plan: Follow a three-step process of self-assessment, phase sequencing, and integrating supporting pillars like nutrition and recovery.

- Put It Into Practice: See how these principles apply to real-world goals with sample plans for destinations like the Red River Gorge and Yosemite, and get access to a downloadable planning worksheet.

Why Does Structured Training Work? The Science of Periodization

Structured training isn’t about magic formulas; it’s applied sports science. Understanding why it works is the first step toward making it work for you. Periodization provides a logical roadmap for your body’s adaptation process, ensuring that every ounce of effort is channeled toward tangible, long-term improvement. It’s the difference between wandering in the wilderness and following a map to the summit.

What is the Core Principle of Periodized Training?

Periodization is the systematic planning of athletic training. At its heart, it’s the methodical manipulation of training variables—like load, volume, and intensity—to maximize performance adaptations and hit a peak performance at a predetermined time. The primary goal is to manage the critical balance between fitness and fatigue. While every workout builds fitness, it also generates fatigue. A smart periodized plan for climbing allows that fatigue to dissipate at key moments, letting your underlying fitness shine through.

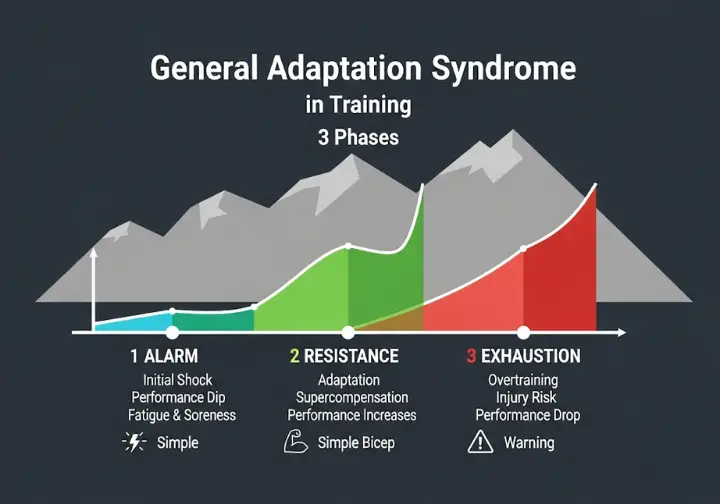

This approach is directly rooted in Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), a model describing the body’s three-phase response to stress: Alarm, Resistance, and Exhaustion. Effective periodization training is designed to keep you in the Resistance phase, where adaptation and growth occur, and steer you clear of the Exhaustion phase, which leads to injury and overtraining. The Current concepts in periodization of strength and conditioning provide a definitive overview of this science, validating how a smart rock climbing training program manages this stress-recovery cycle for optimal gains.

How Do Climbers Actually Get Stronger?

Progress is driven by a fundamental law of physiology: Progressive Overload. To get stronger, you must consistently subject your body to a training stimulus that is slightly greater than what it’s accustomed to. This doesn’t always mean adding more weights; you can achieve progressive overload by increasing volume (more reps), decreasing rest times, or increasing the intensity of the movement itself. This is the engine of all physical adaptation, from building strength for a hard boulder problem to building endurance for a long route.

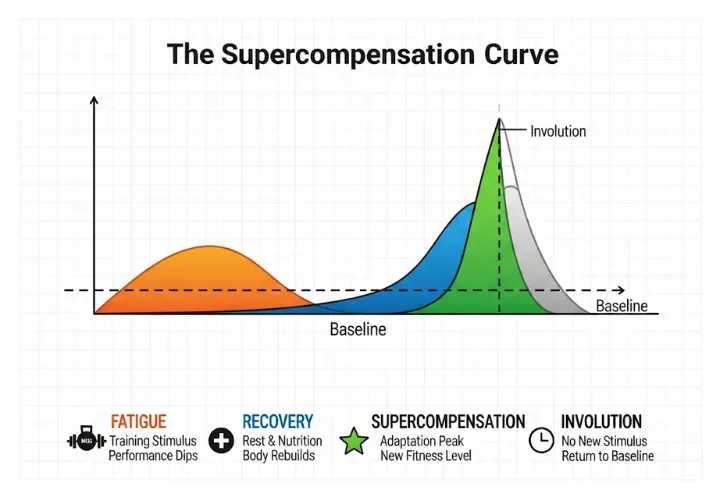

The magic happens during recovery, through a process called Supercompensation. After a targeted workout and adequate rest, your body doesn’t just return to its previous baseline—it rebuilds to a slightly higher level of performance. This physiological rebound effect is how you get stronger over time. A typical training year is built around this cycle. Many plans use three weeks of increasing load to accumulate stimulus, followed by a fourth “deload” week of reduced intensity. This deload is crucial, as it allows for significant supercompensation and prepares you for the next block of training. As this study on the principle of progressive overload shows, load progression is the scientific basis for long-term strength. That’s why Targeted strength training is essential for climbers who want to see real improvement.

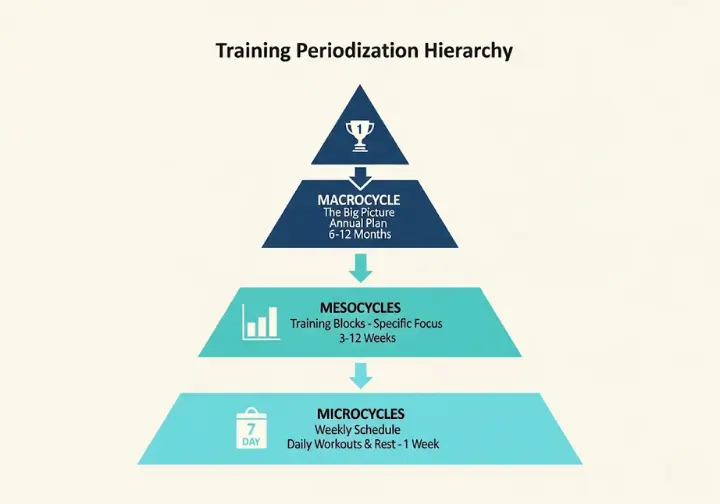

How Is a Full Year of Training Organized?

Periodization uses a clear hierarchy to break down a massive goal like a seasonal training plan into manageable pieces. This structure prevents you from getting lost in the many details and keeps your training focused.

- The Macrocycle: This is your big-picture plan, often lasting six months to a year. It encompasses every phase of training leading up to a major objective, like a bouldering trip to Fontainebleau or a sport climbing trip to Yosemite.

- Mesocycles: These are the distinct training “phases” or “blocks” within your macrocycle, usually lasting 3-12 weeks. Each mesocycle has a singular focus, dedicated to developing a specific quality like Base Building for muscular endurance or a strength development phase for improving grip strength.

- Microcycles: These are the shortest training units, almost always one week long. A microcycle dictates your day-to-day schedule of workouts and rest days. This is where you manage the weekly progressive overload and recovery needed to drive the supercompensation detailed in your mesocycle. Building a plan with this hierarchy ensures your daily efforts align with structured training with clear goals.

Choosing Your Blueprint: Which Periodization Model is Right for You?

Once you understand the ‘why,’ you need to choose the ‘how.’ There isn’t a single perfect periodization model; the best one for you depends on your experience level, your goals, and the time you have. The three primary models—Linear, Block, and Undulating—offer different blueprints for organizing your training. Selecting the right one is a strategic decision that will define your path to peak performance.

What are the Pros and Cons of Linear, Block, and Undulating Periodization?

Each model manipulates training variables differently, resulting in unique advantages and disadvantages.

- Linear (Sequential) Periodization: This is the classic periodization model and the simplest to understand. It focuses on developing one physical quality at a time in distinct, sequential phases (e.g., an endurance block, followed by a strength block, then a power block). This highly effective linear periodization model is great for achieving a single, sharp performance peak for a specific date, but can lead to the detraining of abilities that are not currently in focus.

- Block Periodization: This model is an evolution of linear. A climber still focuses on a primary quality in each block (e.g., maximal strength), but includes a small amount of “maintenance” work for other qualities (e.g., one short endurance session per week). This block periodization approach prevents significant detraining and creates a more well-rounded athlete, but the higher overall volume can increase the risk of overtraining if not managed carefully.

- Undulating (Non-Linear) Periodization: This model, also known as nonlinear periodization, involves much more frequent variation. The training focus changes daily or weekly within each microcycle (e.g., strength day on Monday, endurance day on Wednesday, power on Friday). It is excellent for maintaining all-around fitness and is well-suited for in-season climbers or beginners who need to develop a broad base of skills simultaneously.

| Periodization Model | Core Principle | Best For | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Develops one physical quality at a time in distinct, sequential phases. | Achieving a single, sharp performance peak for a specific date. | Simple to understand and implement; highly effective for peaking. | Can lead to detraining of abilities not currently in focus. |

| Block | Focuses on a primary quality per block, with maintenance for others. | Creating a well-rounded athlete; preventing significant detraining. | Prevents significant detraining; builds a broader base of fitness. | Higher overall volume can increase risk of overtraining. |

| Undulating | Frequent (daily/weekly) variation in training focus within microcycles. | Maintaining all-around fitness; in-season athletes; beginners developing broad skills. | Excellent for maintaining broad fitness; adaptable; good for simultaneous skill development. | Can be complex to program effectively; may not lead to extreme peaks in any one quality. |

The Step-by-Step Guide to Building Your Plan

With the scientific principles and models understood, it’s time to get practical. Building your own effective plan is an actionable, three-step process. This is where you move from theory to execution, translating your goals into a concrete schedule of workouts, rest, and recovery designed to deliver results.

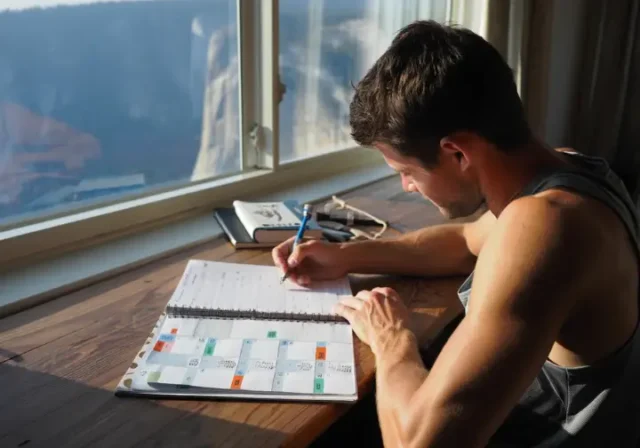

Step 1: How Do You Conduct a Climber’s Self-Assessment?

An effective plan is built on a foundation of honesty. Before you can map out a path forward, you must know exactly where you’re starting from. The goal is to identify your primary limiters—your weaknesses—because training those weaknesses provides the most direct path to improvement.

- Technical Assessment: Video yourself climbing at your limit. Don’t just watch it; analyze it. Look for imprecise footwork, moments where your feet cut loose indicating a lack of core endurance and body tension, and inefficient pacing or flow between moves. Honing your climbing technique is a lifelong pursuit.

- Physical Assessment: Establish objective, repeatable baselines. Key tests include Max Finger Strength (a max weighted hang on a 20mm edge), Pulling Strength (a one or five-rep max weighted pull-up), and Anaerobic Endurance (hangboarding repeaters to failure). The Connection Between Resistance Training, Climbing Performance, and Injury Prevention validates the importance of this type of testing. This is especially true for rock climbing finger training, which is a cornerstone of performance.

- Mental & Lifestyle Assessment: This is just as critical. Use a journal to honestly reflect on your fear of falling, performance anxiety, and internal self-talk on the wall. Are you getting 7-9 hours of quality sleep? Is your nutrition supporting your training? How high are your external life stressors?

Step 2: How Do You Sequence the Different Training Phases?

Training phases, or mesocycles, are not random. They are logically sequenced to build upon each other, moving from general physical preparedness to highly specific climbing fitness. A common mistake is to jump straight into high-intensity power development without building a proper foundation, which is a recipe for injury and burnout.

A well-conceived schedule looks like this:

- Base Building (4-12 weeks): This phase focuses on high volume and low intensity. The goal is to build work capacity and improve climbing technique through modalities like ARCing and Density Climbing. This builds the foundation of endurance climbing.

- Strength (4-6 weeks): The focus shifts to low-volume, high-intensity work. Sessions of Limit Climbing and Max Hangs on a hangboard are used to increase the body’s maximum strength and raw grip strength. Building strength here involves heavy, low-rep exercises.

- Power (3-4 weeks): This phase is about developing explosiveness. Workouts revolve around dynamic bouldering and exercises on a campus board, including plyometric push-ups, to increase the rate of force development, which is crucial for dynamic moves.

- Power Endurance (2-4 weeks): Here, you train your ability to sustain a long sequence of powerful moves. This is where drills like power-endurance bouldering (e.g., 4x4s) and Repeater Hangs come in, targeting your anaerobic energy systems to tackle hard boulder problems.

- Performance/Peaking (1-2 weeks): This involves a taper, where you strategically reduce training volume while maintaining intensity. This sheds accumulated fatigue and allows your body to fully supercompensate, expressing peak fitness for a specific goal climb.

- Rest/Off-Season (1-4 weeks): This phase is absolutely critical for long-term progress. It allows for full physical and mental recovery, focusing on active recovery and antagonist training to prevent imbalances.

As this review on Periodization: Current Review and Suggested Implementation confirms, this logical sequencing is a cornerstone of athletic development. When you get to the Strength and Power Endurance phases, remember that Hangboard training is an effective method to drive specific adaptations.

Climbing Training Phases Explained

A comprehensive breakdown of the different phases in a climbing training cycle, their goals, and typical activities.

Primary Goal

Build work capacity, aerobic endurance, and foundational strength. Improve technique.

Typical Duration

4-12 weeks

Key Training Modalities

High-volume, low-intensity climbing; General strength training (hypertrophy).

Sample Exercises/Drills

ARCing, Density Climbing, Full-body lifts (8-12 reps).

Application to Goal

Sport: Longer ARC sessions.

Bouldering: High-volume circuits.

Primary Goal

Increase maximal force production in fingers and pulling muscles.

Typical Duration

4-6 weeks

Key Training Modalities

Low-volume, high-intensity climbing; Max strength training.

Sample Exercises/Drills

Limit Bouldering, Max Hangs, Weighted Pull-ups (3-6 reps).

Application to Goal

Sport: Focus on strength for crux movements.

Bouldering: The primary focus.

Primary Goal

Increase the rate of force development (explosiveness).

Typical Duration

3-4 weeks

Key Training Modalities

Dynamic, explosive movements.

Sample Exercises/Drills

Dynamic Limit Bouldering, Campus Boarding, Plyometrics.

Application to Goal

Sport: For dynamic cruxes.

Bouldering: Essential for powerful moves.

Primary Goal

Sustain a series of powerful movements. Train anaerobic capacity.

Typical Duration

2-4 weeks

Key Training Modalities

High-intensity intervals with incomplete recovery.

Sample Exercises/Drills

Bouldering 4x4s, Campus Board Sprints, Repeater Hangs.

Application to Goal

Sport: Crucial for steep, bumpy routes.

Bouldering: For long, powerful problems.

Primary Goal

Shed fatigue to express peak fitness.

Typical Duration

1-2 weeks

Key Training Modalities

Tapering: Reduced volume, maintained intensity. Mental preparation.

Sample Exercises/Drills

Light bouldering, one redpoint attempt, Visualization, Rest.

Application to Goal

Both: The final preparation before a trip or competition.

Primary Goal

Physical and mental recovery. Address imbalances.

Typical Duration

1-4 weeks

Key Training Modalities

Active recovery, antagonist training, cross-training.

Sample Exercises/Drills

Yoga, running, swimming, Push-ups, Dips, Shoulder Press.

Application to Goal

Both: Essential for long-term sustainability and injury prevention.

Step 3: How Do You Support Your Training for Optimal Gains?

The hardest training plan in the world will fail without the proper support structures in place. What you do outside of your training sessions is just as important as what you do during them. Nutrition and hydration, sleep, and intelligent plan adjustments are the pillars that uphold your progression.

- Performance Nutrition: Your nutrition should be periodized just like your training. Ensure you consume adequate carbohydrates before training to fuel your sessions. Within two hours post-training, consume a mix of carbs and protein (a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio works well) to replenish glycogen stores and initiate muscle repair. While some climbers explore a high protein, high fat, low carb (HPHFLC) diet for climbers, ensure your choice aligns with your current training demands.

- Recovery Protocols: Sleep is your single most powerful recovery tool. Aim for 8-10 hours per night during heavy training blocks. Incorporate active recovery like light cardio on rest days to promote blood flow, and use soft tissue work like foam rolling or forearm massage to aid in fatigue and recovery.

- Autoregulation: No plan survives contact with reality. Autoregulation is the practice of adjusting your daily training based on how your body feels. Use simple scales like Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) or Reps in Reserve (RIR) to adjust the load up or down, ensuring the day’s training matches the intended intensity and prevents overtraining.

Putting It All Together: Sample Plans and Resources

Theory is valuable, but seeing it in practice is what makes it click. Let’s look at how these principles can be applied to two common climbing goals. The key takeaway is not to copy these plans verbatim, but to understand the logic behind their structure so you can build your own plan… read on.

What Does a Periodized Plan Look Like for a Specific Goal?

The structure of your plan should be dictated by the demands of your goal. A climbing trip focused on long, pumpy sport routes requires a different peak than a trip focused on powerful, low-move boulder problems.

- Red River Gorge Sport Climbing Trip (12-Week Linear Plan): The steep, endurance-oriented routes in The Red River Gorge (RRG) in Kentucky demand a high level of power endurance. A classic 12-week linear periodisation plan would be perfect. It would sequence a 4-week Base phase (ARCing, Density Climbing), a 4-week Strength phase (like limit bouldering), a 2-week Power Endurance phase (4x4s), and a final 2-week Taper to arrive at the crag feeling strong and rested.

- Yosemite Trad/Big Wall Trip (16-Week Block Plan): A major trip to Yosemite for trad climbing or a big wall requires a broad base of fitness. A block periodization model works best here. For example: a 6-week Strength block (with endurance maintenance), a 6-week Power block (with strength/endurance maintenance), and a final 4-week phase focused on performance simulation and tapering.

- The Climber’s Annual Planning Worksheet: The ultimate resource is one you create yourself. To make this process seamless, we’ve developed a downloadable worksheet that guides you through every step: goal-setting, conducting your self-assessment, and laying out your macrocycle to build a personalized schedule.

Your Interactive Training Plan Tool

Visualize your path to success. Use our interactive tool to explore sample 12-week and 16-week training plans for different climbing goals. Check off each phase as you progress and download a PDF copy for reference.

Conclusion

The path to breaking through your climbing plateaus is paved with intention and structure. Moving from unstructured exercise to a scientifically-backed, periodized training program is the single most effective change you can make to guarantee long-term progress. The process is a logical one: begin with an honest self-assessment of your weaknesses, choose a periodization model that fits your life and goals, and then sequence your training phases to build from general fitness to sport-specific power.

Remember that this plan is a living document. True success is impossible without supporting your hard work with intelligent nutrition, prioritizing sleep for recovery, and using autoregulation to adapt your plan to the realities of life. Your best climbing days are ahead of you, and it starts with a plan.

Download our free Climber’s Annual Planning Worksheet to start building your most effective training year ever, and share your biggest training questions in the comments below.

Frequently Asked Questions about Periodization for Climbers

What is periodization in climbing?

Periodization is a way to set up your training into logical cycles. The goal is to manage fatigue, maximize physical adaptations like strength and endurance, and time your peak for specific performance goals, such as a climbing trip or competition. It involves organizing your training year into large macrocycles, focused mesocycles (or phases), and weekly microcycles.

What are the main phases of a climbing training plan?

The main phases are sequenced to build upon each other for optimal results. A typical progression includes Base Building (for general endurance and work capacity), Strength (for maximal strength), Power (for explosive movement), Power Endurance (to sustain difficult sequences), Performance/Peaking (a taper to maximize freshness), and a dedicated Rest/Off-season for full recovery.

Should a beginner use periodization?

Absolutely. A simple linear or undulating periodization model is highly effective for beginners. It provides a clear, structured way to build a strong foundation across all areas of climbing fitness—technique, strength, and endurance—while having a lower risk of the overuse injuries that can come from unstructured, high-intensity training.

How often should you have a recovery or “deload” week?

A common and highly effective structure is to schedule a deload week every fourth week. This means you would have three weeks of progressively increasing training intensity or volume, followed by one week of significantly reduced load. This cycle of four week blocks allows your body to fully recover and supercompensate, which is what leads to significant fitness gains for the next training block.

Risk Disclaimer: Rock climbing, mountaineering, and all related activities are inherently dangerous sports that can result in serious injury or death. The information provided on Rock Climbing Realms is for educational and informational purposes only. While we strive for accuracy, the information, techniques, and advice presented on this website are not a substitute for professional, hands-on instruction or your own best judgment. Conditions and risks can vary. Never attempt a new technique based solely on information read here. Always seek guidance from a qualified instructor. By using this website, you agree that you are solely responsible for your own safety. Any reliance you place on this information is therefore strictly at your own risk, and you assume all liability for your actions. Rock Climbing Realms and its authors will not be held liable for any injury, damage, or loss sustained in connection with the use of the information contained herein.

Affiliate Disclosure: We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. We also participate in other affiliate programs. Additional terms are found in the terms of service.