In this article

Understanding sport climbing grades is fundamental for safety, charting your progress, and truly enjoying the vertical world of sport climbing. However, with a variety of climbing grading systems used across the globe, it can often feel like navigating a complex code. This article will clearly provide sport climbing grades explained, covering the three major international systems: the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS), the French system, and the UIAA scale. We’ll delve into their structures, compare them, and discuss how you can practically apply this knowledge of difficulty ratings sport climbing relies on, whether you’re engaging in climbing locally or planning an international adventure. Let’s demystify these numbers and symbols so you can focus on your climb. This guide offers an understanding sport climbing grades: a global comparison (yds, french, uiaa).

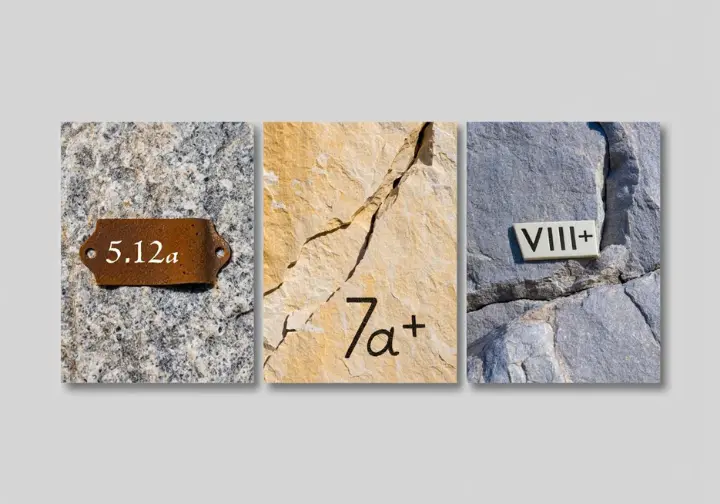

The Global Trinity: A Deep Dive into YDS, French, and UIAA Systems

This section provides a comprehensive explanation of each of the three major sport climbing grading systems. We will cover their individual characteristics before comparing them. The aim is to build a foundational understanding of how each sport system operates independently, laying the groundwork for understanding their relationships and practical applications in the climbing world, from local sport climbs to international climbing adventures.

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS): North America’s Standard

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS), or american yds system, is the main climbing grade system you’ll encounter in North America, especially within the USA. Its origins trace back to earlier Sierra Club systems in the 1930s and 1950s, with significant development occurring at Tahquitz Rock, contributing to the rich history of rock climbing. A detailed exploration of YDS history and structure reveals its evolution. For a look into early YDS development, further resources are available.

When we talk about sport-climbing, our focus within YDS is on Class 5 ratings, which signify technical climbing. This is distinct from other classes that describe hiking or scrambling. These Class 5 ratings begin at 5.0, representing the easiest technical climbs, and are currently open-ended, reaching up to an impressive 5.15d yds grade. This open-endedness allows the system to accommodate the ever-increasing achievements of climbers. For example, the system is applied to technical rock climbing in Yosemite, its namesake region.

Starting from the 5.10 level, you’ll notice lettered subdivisions (a, b, c, d) – these are sub-grades – such as 5.10a or 5.11c. These letters provide finer distinctions in difficulty within that numerical grade (climbing). While plus (+) or minus (-) modifiers are sometimes seen, they are less formally integrated into sport climbing grades compared to their use in traditional climbing. The YDS grade on a sport climb primarily reflects the technical difficulty of the single hardest move or sequence. Though YDS also incorporates climbing protection ratings (G, PG, R, X), these are more relevant to traditional climbing protection, describing the risk and quality of protection, a lesser concern on well-bolted sport-climbing routes.

The French System: Europe’s Numerical Standard for Sport

The French grading system is the dominant standard across much of Europe, particularly in France, and has gained global recognition as a benchmark for sport climbing difficulty. The french sport climbing grades evolved from the UIAA system during the 1980s, placing a stronger emphasis on pure technical difficulty, which is ideal for sport climbing. You can find a good French grading system overview for more context. The French sport systems are widely adopted.

This system employs Arabic numerals, currently ranging from 1 up to 9c+ (an exceptionally high top grade). To offer more detailed distinctions within each numerical french sport grade, lettered subdivisions (a, b, c) are utilized—for example, 6a, 7b (like an f7a sport route), or 8c. Further granularity is achieved by adding a plus (+) sign, such as in 6b+ or 7c+, indicating a slightly harder variation within that letter grade. The Verdon Gorge, with its impressive sport-climbing rock-routes, played a crucial role in the development and application of these numerical sport climbing grades. French climbers and visitors venturing into sport climbing in Europe will frequently encounter this system.

Much like the YDS in sport climbing, the French grade predominantly quantifies the technical difficulty of the crux, or hardest move or sequence, on a route. It is designed as an open-ended system, capable of expanding to accommodate ongoing advancements as climbers continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible in modern sport. The french scale is a key part of many grade systems worldwide.

The UIAA Scale: The Mountaineering Federation’s Approach

The UIAA (International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation) scale is commonly used in Germany, Austria, Eastern Europe, and for some alpine climbing applications, influencing certain alpine grades. Formally adopted in 1967, it built upon Willo Welzenbach’s earlier german scale and was officially made open-ended in 1985 to accommodate rising standards. The UIAA itself is a significant international body with numerous member federations, dedicated to promoting safety and standards in mountaineering and climbing globally, sometimes influencing a national climbing classification system. Lucien Devies was influential in its global assessment scale, while Francois Labande helped parameterize the French scale with it.

The UIAA scale uses Roman numerals (I, II, III, etc.), with uiaa roman numerals like grades i, ii, and so on, currently extending to XII+ for the most challenging climbing routes. For finer gradations within a Roman numeral uiaa grade, plus (+) or minus (-) signs are employed, such as VI+, VII-, or IX. You can consult the official UIAA grading scale and their documents on UIAA scales of difficulty for precise details. While it can be applied to sport climbing, its historical roots are deeper in traditional climbing and alpine climbing, sometimes leading to a more holistic feel in its application, though for bolted routes, technical difficulty remains key. Understanding mountaineering and climbing standards connects to the UIAA’s broader scope and its uiaa grade system.

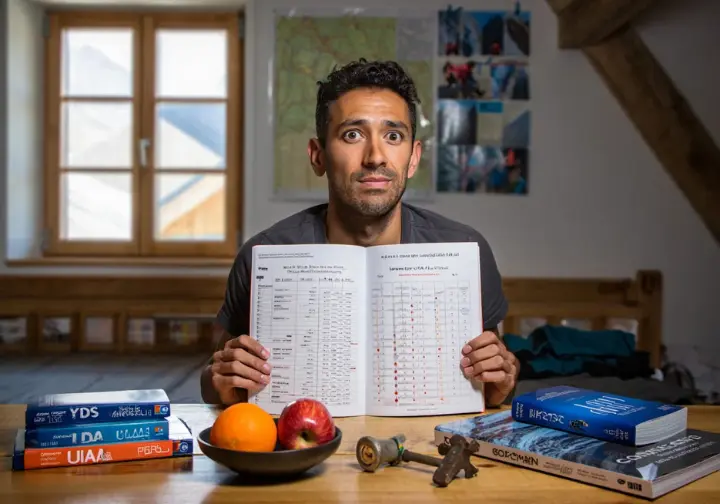

Comparing Apples, Oranges, and Pitons: The Grade Conversion Challenge

This section directly tackles a primary concern for many climbers: how YDS, French grades, and UIAA grades stack up against each other in a climbing grade comparison. We will present a conversion chart and, just as importantly, discuss the inherent complexities and limitations of trying to make exact translations between these systems offering different difficulty grades.

The All-Important Grade Conversion Chart

A grade conversion chart, often a comparative grades table, is an indispensable tool for climbers navigating different regions or guidebooks that utilize varied systems. It offers an approximate translation of difficulty levels between YDS, French (Sport), and UIAA rock climbing grades. Such charts typically display equivalencies from beginner levels (e.g., YDS 5.0-5.4, French 3-4, UIAA I-IV) up to the current elite grades (e.g., YDS 5.15d, French 9c, UIAA XII+). This directly answers common questions like, “How does a 5.11a (YDS) compare to a French grade?” or for a general YDS to French conversion.

The data for these charts is usually compiled from a consensus of reputable sources, including climbing organizations and widely recognized climbing information websites; a comprehensive international grade comparison chart is a good reference. It’s always wise to consult multiple sources of climbing grade conversion data for a balanced perspective on international grade comparison. For instance, a chart might show that a YDS 5.10a is roughly equivalent to a French 6a or a UIAA VI+. However, it is critical to remember this is an approximation and should be used with an awareness of its limitations, a key aspect when planning international climbing trips.

Why Conversions Are Not Absolute: Understanding Nuances

Direct grade conversions are inherently limited due to system-specific nuances and the distinct historical development paths of each grade (climbing) system. For example, the YDS evolved largely independently in North America, while the French system branched off from the UIAA scale in Europe, each carrying slightly different philosophical underpinnings regarding what defines difficulty. The challenges in grade conversion are well-documented when looking at comparative grading scales.

What each system prioritizes can differ subtly. YDS historically incorporated elements pertinent to traditional climbing risk, whereas the French system strongly emphasizes pure technical grades for sport climbing. Moreover, local grading cultures can significantly impact how a grade feels in a specific climbing area, regardless of the system used. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “sandbagging” (harsher grading) or “soft” grading, addresses why grades can feel inconsistent between different crags or regions. You might find some statistical analyses of grading scales that delve into these variances in grade contexts.

Therefore, any conversion chart should be viewed as a guideline, not an absolute rule. A climber’s individual strengths, weaknesses, height, reach, and preferred style also heavily influence their perceived difficulty of a route. What feels like a 5.10 to one person might feel harder or easier to another for a particular climb.

The Subjective Science: How Routes Get Their Grades

This section delves into the often-debated topic of subjective sport climbing grades. We’ll explore the process of how rock climbs grades are assigned and the various factors that contribute to their inherent variability. This addresses a key “problem-solving” aspect for climbers trying to understand why climbing grades can feel inconsistent.

The Role of First Ascensionists and Community Consensus

Typically, the first ascensionist—the individual who initially completes a free climb of a route—proposes an initial grade. This grade is based on their perception of the route’s difficulty, often influenced by their personal strengths, weaknesses, and extensive experience on other established climbing routes. Learning how climbing routes are rated involves understanding this initial step.

Over time, as more climbers repeat the route, a community consensus in grading tends to form regarding its true difficulty, sometimes after many repeated ascents. This consensus may confirm the initial grade or lead to adjustments, either upwards or downwards. This process is dynamic and can sometimes involve considerable debate, especially for routes at the cutting edge of difficulty or those with unique or awkward styles of movement. Online climb-logging platforms and modern guidebooks play a significant role in reflecting this evolving consensus. While the “overall feel” of a route can subtly influence grading, for sport climbing, the crux difficulty remains paramount in systems like YDS and French. This process is part of broader climbing community ethics and practices.

Factors Influencing Grade Perception: Beyond the Numbers

Numerous overall grade factors contribute to the subjective perception of a climbing grade. Climber morphology, such as height, reach, and even finger size, can make certain grades feel easier or harder for different individuals. What might be a long reach for one climber could be a simple extension for another. This inherent subjectivity of climbing ratings is a core aspect of the grading discussion.

A climber’s preferred style—for instance, whether they excel on crimps versus slopers, or on overhanging terrain versus slabs—heavily influences how difficult they perceive a route of a given grade. Specific rock types also present characteristic hold types and movement styles that can affect perceived difficulty for a specific rock climbing experience. Furthermore, local grading traditions play a significant role; some areas are notorious for “stiff” or “old school” grades (feeling harder than the number suggests), while others might be considered “softer”. Even prevailing conditions like temperature and humidity can affect friction and thus perceived difficulty. The difference between indoor grading in climbing gyms and outdoor grades is another common point of variance, as gym bouldering grades or indoor climbing route grades are set by individuals and may not always align perfectly with outdoor consensus for a given grade. Exploring gym versus outdoor grade perception can shed more light on this.

“Old School” vs. Modern Grades: A Historical Shift

Particularly within the YDS, there’s often a noticeable difference between “old school” grades and modern interpretations of the same numerical grade. Many routes established in the early days of the YDS, perhaps in the 1960s and 70s, especially before the 5.10 barrier was consistently understood and applied, can feel significantly harder than contemporary routes carrying the same grade. The history of climbing grades and subjectivity offers context here.

This discrepancy arises because the understanding and calibration of the upper end of the grading scale evolved over time. As climbers relentlessly pushed standards, the perception of what constituted a 5.9 or 5.10, for example, naturally shifted. Iconic climbs from earlier eras often established the benchmarks for their grades at the time of their first-ever climb. For instance, Tahquitz Rock’s “Open Book” was a benchmark 5.9 in its day, a significant achievement at the time. Information on grade milestones in rock climbing can illuminate these historical benchmarks. Climbers should be aware that older guidebooks or routes established decades ago might feel “sandbagged” (harder than rated) compared to contemporary climbs. This historical context is vital for route selection and managing expectations appropriately.

Practical Application: Using Grade Knowledge Effectively

This section offers actionable advice for climbers on how to use their understanding of grading systems for route selection, international climbing, and tracking progress. It aims to directly address the practical application micro-intents, helping climbers translate theoretical knowledge about global difficulty levels into tangible benefits for their climbing experiences.

Selecting Appropriate Routes: Matching Skill to Challenge

Understanding grading systems is vital for selecting climbing routes that align with a climber’s current skill level, ensuring both safety and a positive climbing experience. Attempting routes that are excessively difficult can lead to frustration or even dangerous situations, while routes that are too easy may not provide adequate challenge for progression. Guidance on understanding route grades for selection can be very helpful.

Climbers should use grades as a guide to identify potential projects or routes within their comfort zone, particularly when exploring new areas or different types of rock. This is a cornerstone of appropriate route selection. It’s important to consider not just the numerical grade but also available information about the route’s character—such as whether it’s a slab, overhang (requiring steep climbing technique), sustained, or cruxy—as this can influence the actual difficulty experienced. For those new to the sport, focusing on selecting routes for beginner climbers is a critical first step. Tracking personal progression involves noting the grades of successfully climbed routes and identifying areas for improvement in climbing technique or stamina, which helps in setting realistic goals for future climbs. Many find climbing ratings explained for beginners useful.

Navigating International Crags: A Climber’s Passport to Grades

When climbing internationally, familiarity with the local grading system and its general comparison to your home system is indispensable. This often involves using conversion charts as a starting point but also being prepared for regional variations in how grades are interpreted. Knowing which grading system is predominant in your destination country—for example, French grades in much of Europe or YDS in the USA—is a primary step in planning your trip. For more on interpreting grades when traveling, specific resources can be enlightening.

Beyond conversion charts, it’s advisable to research specific climbing areas or even individual crags within a region, as local grading customs can vary significantly. Reading forums, guidebook descriptions, and talking to local climbers can provide invaluable insights into the nuances of an area’s grading. For instance, understanding grades is key for climbing in international destinations like Spain. When climbing in an area with an unfamiliar grading system or one known for stiff grades, it’s wise to start conservatively. Gradually increase the difficulty as you develop a personal calibration to the local interpretation of grades. You can find good information on international climbing grades conversion.

Developing Personal Calibration and Understanding Limitations

Ultimately, climbers develop a “personal calibration” to grades through experience across different rock types, climbing styles, and geographical areas. This involves recognizing how your individual strengths (e.g., finger strength, endurance) and weaknesses align with the demands of routes at various grade levels. It is crucial to remember that grades are subjective indicators, not absolute measures of difficulty. For those just starting, REI offers beginner friendly climbing ratings information.

Factors like how well-rested you are, current weather conditions, and even your mental state can affect how hard a climb feels on any given day. Use grades as a tool for communication and general difficulty assessment, but try not to become overly fixated on the numbers themselves. The enjoyment and physical challenge of the climb itself are paramount. Be aware of the distinction between sport climbing grades and grades for other disciplines like bouldering grades (which uses systems like the V-Scale or Font Scale, sometimes called v-grade or american v-scale) or traditional climbing, which often includes risk or seriousness assessments like UK E-grade or YDS protection ratings. These systems, including alpine grading systems, measure different aspects of the climbing experience, from a one-day climb to multi-pitch climbing. For further understanding climbing grade systems, various resources are available. Clarifying the distinction from traditional climbing grades is also important, as YDS is used for both but with different implications for roped climbing.

The Evolving Benchmark: Historical Roots and Future of Grading

This section delves into the historical development of these grading systems and looks forward to potential future trends in assessing climbing difficulty. This provides richer context and satisfies curiosity about the evolution of grades, a story of innovation and ever-rising standards in climbing grading.

A Brief History: The Genesis of Modern Grading Systems

Climbing grades didn’t appear overnight; they evolved as climbers sought more precise ways to communicate route difficulty. Early systems were often simpler and more localized to specific regions or crags. The evolution of climbing grading is a fascinating topic within the broader history of rock climbing.

The YDS arose in North America from Sierra Club efforts in the 1930s, undergoing significant refinements at Tahquitz Rock in the 1950s by influential figures like Royal Robbins and Yvon Chouinard. Yosemite Valley subsequently became a crucial proving ground for these grades. The UIAA scale, formalized in 1967, has roots in the Welzenbach Scale from the early 20th century and became open-ended in 1985. The American Alpine Club offers insights into the UIAA climbing classification system history, a key part of any national climbing classification. Later, the French system diverged from the UIAA system in the 1980s to better suit the burgeoning sport climbing scene, focusing more on pure technical difficulty. The open-ended nature of these scales is a critical feature, allowing them to adapt as climbers continuously push standards and achieve new levels of difficulty, marked by milestone ascents. These pioneering efforts in climbing development by key individuals helped shape the systems we use today.

Pushing Boundaries: Current Top Grades and Milestone Ascents

The top end of climbing grades continues to evolve as elite athletes achieve remarkable feats of strength, skill, and dedication. Currently, the hardest recognized sport climbing grades hover around YDS 5.15d, French 9c, and UIAA XII+. Information about current hardest climbing grades is readily available for those tracking the current hardest climb.

Milestone ascents serve as crucial benchmarks for these upper grades. For example, Adam Ondra’s ascent of “Silence” (proposed 9c French / 5.15d YDS) and Sébastien Bouin’s “DNA” (also proposed 9c) represent the current pinnacle of sport climbing difficulty. These routes, like the world’s hardest climbs, captivate the climbing community. Historically, routes like Wolfgang Güllich’s “Action Directe,” often cited as the world’s first 9a (French), were groundbreaking achievements that redefined what was thought possible. You can find many elite climber perspectives on grading and these historic ascents. The process of confirming these top grades often takes time and requires subsequent ascents by other elite climbers, adding to their legendary status. These achievements highlight the open-ended and progressive nature of climbing difficulty scales. Organizations like the American Alpine Club (AAC) and the UIAA play roles in documenting and discussing climbing standards and achievements through their publications and global networks.

The Future of Grading: Standardization Efforts and Technology

There are ongoing discussions and research into making climbing grade assessment more objective and standardized globally. This directly addresses the inherent subjectivity that can lead to inconsistencies across regions and even within the same climbing area. Some research on climbing grade standardization is exploring these avenues, potentially using sports technology.

Initiatives like the International Rock Climbing Research Association (IRCRA) have proposed scales and methodologies for collecting more standardized data on climbing performance and route difficulty, primarily for research purposes. Emerging technologies, including Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), are being explored for their potential to analyze climbing movement and assess route difficulty with greater objectivity. For instance, Stanford has explored AI in climbing grade classification using computer vision. Tools like “Darth Grader” represent attempts to use data analytics to provide more nuanced grade insights. While a single, universally adopted global grading system seems unlikely in the near future due to deep-seated historical and cultural factors, these research efforts and technological advancements may lead to a better understanding and more consistent application of the existing systems we use for grades rock and other climbs.

Key Takeaways: Navigating the World of Climbing Grades

This journey through the complexities of sport climbing grades aims to equip you with practical knowledge. Understanding these systems enhances safety, informs route selection, and enriches your overall climbing experience, from local crags to international adventures, improving your understanding of global level difficulty.

YDS, French, and UIAA are the three primary sport climbing grading systems, each with its unique structure and geographical prevalence, but all ultimately striving to quantify technical difficulty. Mastering their basics is a fundamental step for any serious climber. While grade conversion charts are useful tools, they offer approximate equivalencies; inherent subjectivity, historical divergences, and local customs mean these conversions are never absolute. Grades are established through a combination of the first ascensionist’s proposal and ongoing community consensus, shaped by factors like climber style, morphology, and specific route characteristics.

The practical application of this grade knowledge involves selecting appropriate climbing routes, navigating international climbing destinations with greater confidence, and developing a personal calibration to different grade systems and rock types. Embrace the journey of understanding grades not as a rigid set of rules, but as a dynamic language that enriches your climbing progression and appreciation for the sport’s global diversity.

Frequently Asked Questions about Sport Climbing Grades

What is the single most important factor a sport climbing grade (like YDS or French) tries to measure? >

Are climbing grade conversion charts 100% accurate? >

Why can a 5.10a in one climbing area feel harder than a 5.10a in another, even if they use the same YDS system? >

Do I need to worry about the G, PG, R, X ratings on YDS-graded sport climbs? >

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. We also participate in other affiliate programs. The information provided on this website is provided for entertainment purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, adequacy, legality, usefulness, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information, or about anything else. Any reliance you place on the information is therefore strictly at your own risk. Additional terms are found in the terms of service.